Last night I dreamed I was turning into a goat. It was quite interesting, watching my arm grow a pelt of thick whitish hair, my fingers claw into a cloven hoof. I wasn't perturbed because I knew (in the dream) that this had happened before. The woman next to me, who in some respects resembled my dead sister (our birthdays are in January, a week apart), and who I thought perhaps was ill, admitted she too was undergoing the same metamorphosis ... we fell upon each other with a lust that was, well, goatish. Until my son, who was on the bed with us, asked us to stop because we were interrupting his TV watching. The bedroom was in an annex of the vast terminal of an airport. I went out into the concourse, I had no visa for onward travel ... and where, anyway, does a goat keep his passport? Then I was in a bathroom, hearing my name called in tannoy-speak ... I woke up. All day I have been looking, at odd moments, speculatively, at my right arm. As if awaiting the resumption of that impossible transformation ...

31.12.07

30.12.07

Sumer Hil

Only in certain lights is it possible to see that the spire of the church of St Andrews carries a cladding of clay tablets upon which there is cuneiform writing. I myself have seen it only twice: once after a night on the town, when I was sitting out on my tiny deck drinking a last cold beer before bed, the violent sun rising behind me struck the steeple with its rays and revealed those outlandish and enigmatic markings. I could not really believe what my eyes told me they had seen, and dismissed the apparition as an hallucination consequent upon the long drinking session. That is, until the other night. Once again I had been out, once again I had been drinking, but not to the extent of the previous occasion. In fact, if I had not had, in quick succession, two glasses of absinthe - the real kind, with wormwood in it - just before I left my hosts, I would have said I was more or less sober. The absinthe afflicted me with a strange clarity. Things seen and heard came as if from far away, yet seemed very close. I started to talk and suddenly the whole room was listening. I read a passage from Kenneth Patchen's The Journal of Albion Moonlight and the entire book, which I used to own, came to mind. I said goodbye to everyone and went to return home: as I drove across town, it was green lights all the way. The phone was ringing as I came in and my friend D and I were overtaken by hilarity. It was while I was talking to him that I strayed out onto the deck and saw again, in the violence of the indigo twilight, those equivocal markings. D is, as they used to say, a gentleman and a scholar; he also lives nearby and as soon as I said: they're back! and explained to him what I meant, he decided to come over and bring his camera. He saw them too, he photographed them; and now he has shown his photographs to some Fellow he knows in the Bureau of Lost Languages at Sydney University. This is how I can tell you something of what those tiles mean.

II

D used a telephoto lens, just as I had, on that other occasion, looked at the steeple through powerful binoculars; still, the writing wasn't clear. The most the Fellow could say was that they appeared to be from a version of the Descent into the House of Dust, but whether it was the famous account of Inanna's going down or another, perhaps Enkidu's when he went to retrieve the bat and ball his master Bilgames had lost into a crack in the earth, he could not say. Therefore I have had recourse to ancient documents for this redaction: Kur is above Apsu, the abyssal waters. Those who take that path can never come back. The clawed hand of the demon Humut-tabal drags the reluctant down the Road of No Return and opens the door to the House of Dust. Scorpion men, tall as the sky, guard the way into Ganzir, the seven-gated palace. Here sheep grow no wool, here the inside bolt is covered with dust, because it is never used, because that door never opens again. Belet-seri marks off your name in the Book of the Dead. At each Gate you lose something: hat, coat, belt, shirt, stick, wristwatch, shoes so you arrive naked and bent in the room where the dead sit at long tables eating clay for bread and drinking muddy water instead of beer. They see no light, they dwell in darkness. They are clothed like birds, with feathers, and their wings are bound about them. Everything else is dust. Here is the domain of Ereshkigal and her silent consort Nergal. She tears out her hair like leeks, her face is livid like a cut tamarisk, her lips are dark as the rim of a kuninu-vessel. She has to weep for young men who have abandoned their sweethearts. She has to weep for girls wrenched from their lover's laps. For the infant child, expelled before its time, she has to weep. For her son Ninazu, she weeps eternally. When her sister Inanna came down here Ereshkigal sent out against her sixty diseases: Disease of the eyes to her eyes; Disease of the arms to her arms; Disease of the feet to her feet; Disease of the heart to her heart; Disease of the head to her head ... if you can get past Ereshkigal you may meet the Judge of the Dead. If you have made offerings he may remember you. If you have gifts he will accept them. If your children continue to make offerings you may eat and drink; but you will never cease to hear the sobbing of Ereshkigal as she lies down in the dust of the floor, ripping her long nails down her alabaster breasts, tearing her hair out like leeks.

III

Although our City is only a few hundred years old, it has encoded into its built environment many survivals from antiquity, some as explicit as the Egyptian Needle on the borders of Hyde Park at the end of Bathhurst Street, or the Camperdown Velodrome made after the pattern of the Coliseum; others, such as this I am writing about now, are so deeply encrypted in the texture of things they resist discovery over many years and, even when scryed, continue suggestive, as if their seeming presence were an illusion, as if they are only to be revealed to the delusional. Well, I am used to that, I am always only half in, or half out, of the world, its true face is often shown to me as illusive, its elusiveness often turns to show a true face. Of more concern to me now is an anomaly that I have become preternaturally aware of since viewing D's photographs and hearing what the Fellow at the Bureau of Lost Languages had to say about the script: for as long as I have been here I have wondered about the upper reaches of Hawthorne Canal, where it disappears in a black O under the Railway Bridge, Longport Street and the Mungo Scott Flour Mill. What is beyond that looming darkness, some strange passage to a netherworld? I do not imagine it is an entrance into Kur and why, anyway, would I want to go there? No, what I am remembering is that other occult our City is built across, the dreaming place that never was extinguished, never expunged, never quite forgotten. Sometimes in the evening, when a currawong sits on a television aerial before the lavender sky and carols across the rooftops I almost glimpse a survival of it. Or in the very early dawn when that unknown bird cries out its eerie hoop-hoop-hoop-hoop-hoop ... This lost land is really nothing to me, or at least no more than that dread place figured across the tiles of the steeple. But, equally, since there is no doubt that I will at last, at no cost but that of living, enter the House of Dust or equivalent, why should I not, while I am still living, attempt entry into this other country once called, with what authority I do not know, Alcheringa? It may take me some time to do it, it may take years, but one day I think I will climb down into the graffiti haunted canal and take the way south, under the remains of the old iron whipple truss bridge, under Longport Street, under the Flour Mill and climb up through that dark O towards the source.

25.12.07

Christmas is for the Birds

Day begins in darkness with the outlandish hooping of a bird I can't identify, perhaps a channel-billed cuckoo, aka the Orgasm Bird; later its kawk ... awk-awk-awk echoes past the steeple where a sombre bell is tolling. It's the largest parasitic bird in the world and comes down here every spring from New Guinea to lay its eggs in the nests of magpies or currawongs or crows, whose young it will exponentially outgrow. The red-whiskered bulbuls are nesting, taking dried bits of a dead frond of the palm beside the balcony back around the side of the building somewhere. With their black upstanding crests, red dot under each eye, orange rump, they are innately cheerful, even humorous; their cry always sounds to me like: See three pee-oh, see three pee-oh, as if they were aficionados of Star Wars. They're an Asian bird, introduced around the turn of last century. For the Turks the bulbul is an exemplar of a poet but perhaps that's a different bird - the word, from the Persian, seems to mean nightingale. As I drink my morning coffee I watch a willy wagtail, beating its wings, almost stationary, plucking some quite large insect from in amongst the leaves of the gum tree out the front; while three ibis cross the western sky heading inscrutably south. They always look prehistoric to me, like pterodactyls, and they are indeed an ancient bird. And then I recall hearing on the radio the other day about a facility some kind of corvine bird in North America has for lying: to distract other birds from their favourite food they will give forth their characteristic predator warning cry, scattering their rivals and allowing them to feed undisturbed. There are Indian minas patrolling the orange tiles of the roof of the building next door, with their military strut and insouciant eye for the main chance, whatever it may be. I remember an iridescence of lorikeets yesterday amongst the green leaves of the eucalypt next door, and the shy and beautiful spotted doves that graze the carpark out the back when everyone has gone to work. Also the pair of black-faced cuckoo shrikes, slender and elegant, that perch sometimes on the wires, their blue-grey plumage the colour of an overcast sky, threatening rain. These grey days make all the colours shine; and it's strange to think that our festivals have no meaning for the birds except this: it's so quiet today, the streets deserted, the air and atmos peaceful for once after the clamour and hysteria of the last week, that perhaps it represents an opportunity to make this world more theirs than it usually is, to make themselves more at home. Although it's hard to imagine how more at home they could be, since even the migratory among them are always at home; so maybe what I mean is they have no other home than this and in that way resemble us all, indiscriminately, the homed, the homing, the homesick, the home away from home and the homeless.

23.12.07

21.12.07

19.12.07

Two Unknown Alphabets

I

The last light of March 8, 1914, a Sunday, in Lisbon; a thread of spittle expelled by the Sibyl of the Troad during one of her transports; a grain of sand scuffed up by the shoes of Jan Bockelson of Leyden as he ran through the streets of Munster trying to escape his death by torture in June of 1535; whispers passed into the air near Lake Alice Hospital for the Criminally Insane on January 9, 1954; the electrical path of a willy willy crossing the border between two inchoate territories of New Holland in the epochal year of 1769; a lost verse from the Gospel of St Luke; a flash from the helm of a knight in the army of Saladin, that Kurd from Tikrit, outside of Jerusalem in 1187; fragments of pigment abraded from the painted backdrop of a Punch and Judy Show during a performance on a London street in 1823; a drop of ink that fell from Li Po’s brush after he finished writing Drinking with a Friend in the Mountains in whatever year of the T’ang Dynasty it was; an unidentifiable stain dried off Samuel Pepys’ trewsers not long before the Great Fire; khol that was used as eye shadow by a woman of the zenana of the Last Mogul Emperor, Delhi, 1857; salt from sweat that pearled on Sappho’s breasts; a mote from a sunbeam that shone through a window in Rio de Janeiro, August 24, 1899; a residue of Shakespeare’s unshed tears; amino acids contained in a meteor that fell from Mars; the final babushka in a Russian doll; a portion of Mohamed’s mitochondrial DNA; iridescence of a scarab’s wing from the XIV Dynasty; memories of antediluvian moths; spume from the wake of da Gama’s ships; a mosquito borne virus from New Guinea’s north coast, vectored into the Pacific by the Lapita people; Mondrian’s thought; detritus of every sailor’s tattoo; something (but what?) from the Burgess Shale; trajectory of a cartridge fired from Wm Antrim’s Winchester rifle during the Lincoln County War; the grains of paradise.

II

The name Ligeia; serum from an iron nail hammered into the wood of a fetish from Benin; a hair from the beard of the Great Khan; a yet to be invented Intel chip, infinitesimally small; the closing moments of the year 2012; a morsel from the jaws of one of the gold-gathering ants Herodotus said inhabited the Dansar Plain; a breath of air from out the valley of Shangri La; an e-ticket to the Lost Museum of Atlantis; the egotistical sublime; the dust that closed Helen’s eye; an incisor tooth from the Missing Link; the barb of a feather from the Korotangi; the notation of a fragment of the melody of a love song of the Alma; the McGuffin; Les Fleurs Du Mal; shards of silica from the Pink and White Terraces; a scale shed from the skin of the snake that tempted Eve; the Gordian Knot; ambrosia; the Compleat Angler; the piece of clay from Babylon inscribed An Bar that foretells the conflagration that will end the world; smoke from Einstein’s trains; the anti-twilight; the mask of tragedy; fugitives from the Peruvian zodiac; the profile of a woman glimpsed under streetlights as she turned a corner in the Zeedijk of Amsterdam on the night of September 24, 1979 … which I will remember always and never again see.17.12.07

15.12.07

13.12.07

I think I have no other home than this

R.A.K. Mason, the ur poet of New Zealand modernism, lives in my street. He has the long head, the unruly hair, the old-fashioned clothes, familiar from the photographs. He wears shoes with heel and toe plates that rasp against the pavement when he goes to the wine shop with his khaki canvas knapsack on his back to buy two bottles of cheap red for $11.00 the pair. Or down to St. Vinnies to look through the second hand books for something to read. I met him the other day opposite the dim hallway of his building, at the Red Door Gallery, where a young woman friend was putting him down on the mailing list; that's how I know he goes by the name of Alan these days. He has Parkinson's disease; when he parcels up a manuscript to send off somewhere, he has to stop someone in the street so that they can address it for him, since his hands shake too badly to inscribe any more. I don't know what kind of machine he uses to write with, we haven't yet discussed technical matters. It may be that he has a dictaphone, and that the young woman is his amanuensis. Sometimes when he has been drinking he looks truly frightening: the stumbling abrasive walk, the lumpy flesh, the staring eyes, the impression of wild and inconsolable grief on his face. As if the news that god has died had only just reached this obscure Pontus.

Bernardo Soares, formerly assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, also lives here but I am unsure exactly where, only that it's further up past Alan's place. He is much attenuated from the long journey, much reduced: so thin as to be almost insubstantial. A shadow of the wind. He has no companions and I do not even know what name he goes by now. I see him pass sometimes in the late afternoon, walking with that peculiar gait of his, swayed back from the hips, hunched forward at the shoulders, his neck extended as a counterbalance to the hands thrust deep into the back pockets of his jeans. He will eat alone at one of the cheaper restaurants in the village, drink a half bottle of wine, and walk superstitiously back home on the other side of the street from the one he came down. There isn't much work for a retired assistant bookkeeper in today's world, but Bernardo has always lived half in a dream, so perhaps his lack of occupation doesn't worry him unduly. He too must spend the long solitary evenings writing in his room. When it rains, and the drops gather on the small round glasses he wears, he seems to see a grey throng of people moving up from or down to the ghost ships that pass constantly on the river. And then, and blessedly, it is as if he had never left the Rua dos Douradores, that dim street along the way to eternity.

Bernardo Soares, formerly assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, also lives here but I am unsure exactly where, only that it's further up past Alan's place. He is much attenuated from the long journey, much reduced: so thin as to be almost insubstantial. A shadow of the wind. He has no companions and I do not even know what name he goes by now. I see him pass sometimes in the late afternoon, walking with that peculiar gait of his, swayed back from the hips, hunched forward at the shoulders, his neck extended as a counterbalance to the hands thrust deep into the back pockets of his jeans. He will eat alone at one of the cheaper restaurants in the village, drink a half bottle of wine, and walk superstitiously back home on the other side of the street from the one he came down. There isn't much work for a retired assistant bookkeeper in today's world, but Bernardo has always lived half in a dream, so perhaps his lack of occupation doesn't worry him unduly. He too must spend the long solitary evenings writing in his room. When it rains, and the drops gather on the small round glasses he wears, he seems to see a grey throng of people moving up from or down to the ghost ships that pass constantly on the river. And then, and blessedly, it is as if he had never left the Rua dos Douradores, that dim street along the way to eternity.

4.12.07

Damascene

Many years ago, when I lived on the shores of Blackwattle Bay, a big triangular tapestry moth appeared one day in my apartment. It settled on the glass of a print, in the white between frame and image, and seemed to have chosen this spot deliberately to augment that austere work with its damascene opulence. When I looked more closely however, I could see its wings were frayed at the tips and edges, that the dust of its camouflage was thinning, falling. The moth disappeared as silently, invisibly, as it appeared; but in each subsequent place I lived for the next twenty years—I can think of eight apparitions—another tapestry moth would unpredictably appear then disappear just as this one did, every one with its wings thinned to a whisper; so that I came to think that each must also leave behind the spore of the next somewhere amongst my small collection of things. This came to an end, or so I thought, five years ago. I went overseas, returned, moved again, abandoning almost all of my possessions, along with the moth and the moth’s memory. And yet ... the other day when I went out my front door in the morning, there was a tapestry moth fluttering in the stairwell. It had been settled, my opening door disturbed it. I watched its agitation for some time, waiting for it to come to rest; it seemed particularly attracted to the bland dark brown wood of my front door but could not, in that superstitious way moths have, bring itself to alight there. I looked for it when I returned but it was not to be found. Then, yesterday, happening to glance up as I went into my study, I saw a tapestry moth on the cream-pink wall above the door, with its intricately patterned wings, its red false eyes, its feathered antennae, its miraculous dust. It too was thinned and frayed, it too was just a whisper in the face of invisibility. Today it was gone as if it had never been, leaving only a trace of Keats—deep-damask'd wings—on the air. And, though this may be both fanciful and entomologically incorrect, the spore of its heir somewhere among my books.

3.12.07

a visitation

My kids were up this weekend. Jesse, the older boy, was telling me how he got in trouble with the bus driver - they catch the bus to school, it visits their village and Patonga, the next one down, before winding back over the hill to Umina. One of the things the kids have been doing is gathering flowers by the roadside and decorating the windows of the bus with them. Hibiscus, mostly, from what I could tell. The driver tolerates this but one day some of these flowers were left strewn on the ground and he became annoyed. I don't think it was serious.

Anyway, I was asking Jesse about this and he was telling me where and how they pick the flowers, when his eyes took on a faraway look and his expression became a bit otherworldly. There were these white flowers, he said. Too high up for me to pick. They were whiter than the whitest white and when I looked at them I had a feeling like some god was near.

He couldn't say what kind of flower they were but later, when we were out walking, Liamh, the younger one, pointed out some that were like those other ones. I asked Jesse again about what he meant: Did you say God was there? I asked. No, he said, it was like a god was near.

Anyway, I was asking Jesse about this and he was telling me where and how they pick the flowers, when his eyes took on a faraway look and his expression became a bit otherworldly. There were these white flowers, he said. Too high up for me to pick. They were whiter than the whitest white and when I looked at them I had a feeling like some god was near.

He couldn't say what kind of flower they were but later, when we were out walking, Liamh, the younger one, pointed out some that were like those other ones. I asked Jesse again about what he meant: Did you say God was there? I asked. No, he said, it was like a god was near.

25.11.07

Lake Dieri

Doris Lessing is someone whose advice I've tried to follow since my grumpy older sister, who in some respects resembles her, handed on The Golden Notebook to me in, I don't know, 1969 or 70. It seems incredible that I read that book then but I did, even though I remember nothing about it. The Four Gated City left stronger traces but they too are faint.

When I wasn't much older I read some exasperated comments she made about writing. It was to the effect that she kept meeting people who claimed to be writers but when she asked what they had written, or were writing, the answer was: Nothing much. A writer should write, she snapped. That particular comment made me blush secretly for years, because I was one of those nothing much kind of writers.

In a mellower mood she once remarked on the peculiar way that, when you are researching or otherwise engaged with a subject, things to do with it come unexpectedly into view. The role of coincidence in research is a subject that might make for an interesting essay. Maybe it's just a function of attention but maybe it's equally a function of inattention. Sometimes the things you need come to hand precisely when you aren't thinking about them.

Today I was a bit hungover but I was happy. It was as if a metaphorical (= real) jackboot had just been lifted from the back of my neck. Not just mine. After writing up a few notes I made in the State Library yesterday, I thought I'd go for a swim before lunch. A dozen laps of the Ashfield pool, during which I collided with a back-stroking Chinese man. Later we stood at the shallow end and chatted. We are the same numerical age but he is a Snake while I am a Rabbit. I hope I bang into you again, I said, making him laugh and demur at the same time.

There's a couple of second hand bookshops along from the pool. The one further towards Croydon belongs to a bookbinder who sometimes works away at his table there but today was just idling. I browsed a book on the Darling (The Ugly River), another on Atlantis, saw that he has a Shorter Oxford Dictionary for sale that I might have to go back for (the 1969 edition, a bargain at $70.00). A young Chinese woman was looking for a vernacular dictionary. She was a Mandarin speaker. I mentioned that our new leader speaks Mandarin. Yes, she said, My husband vote him in! I voted him in too, I said. The bookbinder grinned and murmured in his throat what sounded like: Me too. All Chinese vote him in! the woman said. I told the bookbinder I might come back tomorrow for the dictionary and went down to the other shop.

It's more crammed, more like your typical miscellany. Just as I stepped inside a middle-aged Chinese woman passed in the street, singing out loud, in Chinese, a haunting melody. Things are getting better and better, I thought, intending to move up the back of the shop where the literary texts are. Then I remembered there are usually art books just to the right by the door and turned to those shelves. Right in front of me was a book called The Desert Sea. By Vince Serventy. Who, until his death earlier this year, lived up at Pearl Beach where my kids also live. I spent a revelatory couple of hours with him once, he was critiquing something I'd written.

One of the most persistent impressions I was left with after driving north from Broken Hill through far western NSW was that of a vast, albeit dry, catchment area. You cross literally hundreds of watercourses, all tending in an east west direction. There are beds of dried up lakes, and there are, here and there, dazzling saltpans. Of course everybody knows the absurd trope of an Inland Sea, that chimera so many early explorers looked for in vain. But as we drove through those strangely marine, or at least lacustrine, deserts, it didn't seem so crazy after all. I thought a lot about it on the trip, and subsequently; I looked at maps and in the atlas, and in the end decided that all those ghostly rivers probably, ultimately, flowed into Lake Eyre. Which is dry at the moment but fills up each time a drought breaks.

Well, Vince's book, from 1985, is a history of Lake Eyre, and of its prehistoric precursor, Lake Dieri. Lake Dieri was huge. It was a veritable Inland Sea. Everything west of the Great Dividing Range as far as ... two bastions of ancient rocks to the west of the continent. In the Miocene it was open to the sea, the bones of dolphins have been found. And crocodiles. That part of the trip, up the Silver City Highway to Tibooburra and then on through Sturt National Park into the Channel Country of south west Queensland, in fact took us along the eastern margins of Lake Eyre's enormous catchment, fully one sixth of Australia. As well as through the antediluvian bed of Lake Dieri. Coincidentally, or perhaps not, that drive, that country, is what I'm hoping to write up this week. So I was very happy to buy The Desert Sea, for $5.00, and bring it home to read on a sultry Sunday afternoon, the first of the Mandarinate.

20.11.07

16.11.07

Sometimes

... I don't know just where I am. Am I in the public bar at Maiden's Hotel, Menindee, watching a TV upon which is Doris Lessing looking grumpy about getting the Nobel prize? Or am I in the dining room next door examining a brick from the original hotel upon which someone has painted a view of the hotel in which there is a brick upon which someone has painted a view of the hotel ... ? Or wandering down Emerald Street in South Melbourne looking for real clues to the fictional Cody's Boarding House that I wrote was here? Why do I keep thinking I am at the heart of the oneiric pantopticon that once stood where the old Darlinghurst Gaol is now? (You can see it, the panopticon, in a view of old Sydney Town in a show now on at the Museum of Sydney.) Maybe I'm standing at Dost Mohamed's grave out on the lonely plains where he used to pray, with the two tombstones, one old and faded and beautifully unreadable, the other a brand-new slab with the identical letters cut incisively into it. Or on top of the slag heap that over looks, looks over the Victorian-Colonial town of Broken Hill. (They'll mine that slag heap again one day, for sure. Even if they have to take down the Miners Memorial to do it.) Or perhaps I'm at the bottom of Myall Street, Balranald, on the banks of the Murrumbidgee, gazing down at stars so deep in the depth of black water they are further away than ... the stars. Among the miniature mesas and buttes of the Gol Gol. In a cave on the rocky slopes of Mt. Hope where there used to be a still. Quietly watching purple swamp hens play in the reeds at a Darling bend. Or am I, like they say really, at a Punch & Judy Show on some corner in London Town about, oh, about 1821. Just as Punch persuades the Constable (played by John Howard) to put his own head in the noose. Sometimes ... I just don't know.

14.11.07

7.11.07

Johnny Nation Died

Not driving at the mo', just writing. A different rhythm. Spend the morning piling up words, or stringing them like beads on what seems like an increasingly fragile string - will it hold? - then the afternoons are mine to do what I will. Not much. Often call in at St. Vinnies around lunchtime, why I'm never sure, since there's nothing I really want. Or nothing I know I want.

Today when I went in Christine, the manager, was behind the counter. Her face lit up. Friends of hers had been over staying. From Wanganui. That's where she's from. When I was kid, I told her, growing up in Ohakune, Taihape was our Auckland but Wanganui was our New York. Her friends had given her some names. If he's really a 'Kune boy, they'd told her, he'll know them. Yeah? I went. Johnny Nation died, she said.

Johnny Nation! I said. He was the Mayor. She looked momentarily disparaging. Yeah, she said. But he was also the baker. He was, too. She mentioned his eclairs. His was one of those emblematic names. Along with Mrs Goldfinch, Ben Winchcombe, Frank Woodward, Dr. Jordan. Incommensurable names, that seemed to have the whole world in them.

Christine left the counter and went to the back of the shop, up the stairs, out of sight. I drifted after her towards the shelves of second hand books, wondering if the quiz was over. She was back in a minute, standing above me at the head of the stairs, smiling down. Len and Jim Moule, she read, off a scrap of paper. Know them? I felt the kind of dizziness you get when time collapses. Florence Moule, I said. She was my first girlfriend. We were in love ... even though we weren't old enough to be, we were. She died ...

Florence was a vivid girl, skinny and brown, with straight thick chestnut hair. We loved each other in that childish way that wants to tangle limbs together under the pines or in the long grass. To kick each other's shins below the desk when we sat opposite at long tables in Primer Four. To rendezvous out the back after school and kiss in the shadow of the concrete steps. To just ... be. With each other.

Mole, Christine said. Spelled M O U L E. That right? It was, but I felt there might still have been a doubt there. Her sister, I said. Can't remember her name. She wrote the local history, I've got it at home. I'll show it to you ... took us a while but we got it in the end: Merrilyn George. She teaches at Ruapehu College, where my father did. It's his copy of her book I have, signed and dated: T. C. Edmond, 1990, which is also the year he died.

Christine had met her. She's a smart woman, she said. She is. I've met her too, in the History Room at the Centennial of the Ohakune Primary School, February, 1996. Her beautiful, deep set, slighty hooded eyes had filled with tears when we'd talked about Florence. Whom she resembled more than a little.

Christine said she was going to have a cigarette. I went with her, just up the road, to the bench outside the old Summer Hill Post Office. Sat with her while she puffed on a pre-rolled rollie. I told her about the time Florence picked the top off a wart on her skinny brown knee, how the blood ran down her leg, how hundreds of tiny warts flowered along the path the blood took, on the inside of the calf muscle. How her death from leukemia, sometime in the 1990s also, seemed prefigured in this childhood prodigy.

Don't know what else to say now. Johnny Nation died. So did Florence Moule. Reverberations, insignificant as they may be ... reverberate. Memories are like hunting horns, dying along the wind.

Today when I went in Christine, the manager, was behind the counter. Her face lit up. Friends of hers had been over staying. From Wanganui. That's where she's from. When I was kid, I told her, growing up in Ohakune, Taihape was our Auckland but Wanganui was our New York. Her friends had given her some names. If he's really a 'Kune boy, they'd told her, he'll know them. Yeah? I went. Johnny Nation died, she said.

Johnny Nation! I said. He was the Mayor. She looked momentarily disparaging. Yeah, she said. But he was also the baker. He was, too. She mentioned his eclairs. His was one of those emblematic names. Along with Mrs Goldfinch, Ben Winchcombe, Frank Woodward, Dr. Jordan. Incommensurable names, that seemed to have the whole world in them.

Christine left the counter and went to the back of the shop, up the stairs, out of sight. I drifted after her towards the shelves of second hand books, wondering if the quiz was over. She was back in a minute, standing above me at the head of the stairs, smiling down. Len and Jim Moule, she read, off a scrap of paper. Know them? I felt the kind of dizziness you get when time collapses. Florence Moule, I said. She was my first girlfriend. We were in love ... even though we weren't old enough to be, we were. She died ...

Florence was a vivid girl, skinny and brown, with straight thick chestnut hair. We loved each other in that childish way that wants to tangle limbs together under the pines or in the long grass. To kick each other's shins below the desk when we sat opposite at long tables in Primer Four. To rendezvous out the back after school and kiss in the shadow of the concrete steps. To just ... be. With each other.

Mole, Christine said. Spelled M O U L E. That right? It was, but I felt there might still have been a doubt there. Her sister, I said. Can't remember her name. She wrote the local history, I've got it at home. I'll show it to you ... took us a while but we got it in the end: Merrilyn George. She teaches at Ruapehu College, where my father did. It's his copy of her book I have, signed and dated: T. C. Edmond, 1990, which is also the year he died.

Christine had met her. She's a smart woman, she said. She is. I've met her too, in the History Room at the Centennial of the Ohakune Primary School, February, 1996. Her beautiful, deep set, slighty hooded eyes had filled with tears when we'd talked about Florence. Whom she resembled more than a little.

Christine said she was going to have a cigarette. I went with her, just up the road, to the bench outside the old Summer Hill Post Office. Sat with her while she puffed on a pre-rolled rollie. I told her about the time Florence picked the top off a wart on her skinny brown knee, how the blood ran down her leg, how hundreds of tiny warts flowered along the path the blood took, on the inside of the calf muscle. How her death from leukemia, sometime in the 1990s also, seemed prefigured in this childhood prodigy.

Don't know what else to say now. Johnny Nation died. So did Florence Moule. Reverberations, insignificant as they may be ... reverberate. Memories are like hunting horns, dying along the wind.

2.11.07

rotten glad : part two

Tom's most well, now, and got his bullet around his neck on a watch-guard for a watch, and is always seeing what time it is, and so there ain't nothing more to write about, and I am rotten glad of it, because if I'd a knowed what a trouble it was to make a book I wouldn't a tackled it and ain't agoing to no more. But I reckon I got to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilise me and I can't stand it. I been there before.

31.10.07

29.10.07

You've got 2 chances: Buckley's or none

Portrait of William Buckley (1780-1856) by an unknown artist (after Ludwig Becker), c 1852, La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria.

27.10.07

24.10.07

The Marylebone Coach

It was outside a 1950s milkbar in Broken Hill. It really was a 1950s milkbar. Bell's. The waitresses (two) were plump and wore bouffants and pancake make-up. One was friendly, one wasn't. The decor was impeccable, the provenance too. It was up on the wall in the museum section. Where you bought souvenirs. I had a Jaffa milkshake and it was just like the Jaffa milkshakes I used to have at Gilbert's Dairy in Greytown in 1963. Well, there's slippage all over the place, even in time. My friend had Creaming Soda or was it Vanilla? At Gilbert's (they were Lebanese but I didn't know this at the time), Peter'd put in a squirt of orange and then a squirt of chocolate: that was Jaffa. He'd ask if you wanted ice cream in it or not. But I'm talking about outside, before we went in. Sitting in the hot car waiting for the song to end. That was like the 1950s too, waiting for the song to end. It never did, or it always did, or it still is ending, I'm not sure which. Anyway, the song. Guess who it's by? I'm only going to post the lyrics, the rest is up to you:

I grew up here all of my life

I dreamed someday I'd go

Where the blue eyed girls

And the red guitars

And the naked rivers flow

Now I'm not all I thought I'd be

I've always stayed around

I've been as far as Mercy and Grand

Frozen to the ground

I can't stay here and I'm scared to leave

So kiss me once and then

I'll go to hell

I might as well

Be whistling down the wind

The bus at the corner

The clock on the wall

A broken down windmill

Ain't no wind at all

I yelled and I cursed

If I stay here I'll rust

I'm stuck like a shipwreck

Out here in the dust

(accordion solo)

The sky is red

And the world is on fire

And the corn is taller than me

A dog is tied

To a wagon of rain

And the road is as wet as the sea

Sometimes the music from a dance

Will carry across the plains

The places that I'm dreaming of

Do they dream only of me?

There are places where they never sleep

And the circus never ends

I will take the Marylebone Coach

And be whistling down the wind

So I will take the Marylebone Coach

And whistle down the wind

Afterwards, we just drove away.

I grew up here all of my life

I dreamed someday I'd go

Where the blue eyed girls

And the red guitars

And the naked rivers flow

Now I'm not all I thought I'd be

I've always stayed around

I've been as far as Mercy and Grand

Frozen to the ground

I can't stay here and I'm scared to leave

So kiss me once and then

I'll go to hell

I might as well

Be whistling down the wind

The bus at the corner

The clock on the wall

A broken down windmill

Ain't no wind at all

I yelled and I cursed

If I stay here I'll rust

I'm stuck like a shipwreck

Out here in the dust

(accordion solo)

The sky is red

And the world is on fire

And the corn is taller than me

A dog is tied

To a wagon of rain

And the road is as wet as the sea

Sometimes the music from a dance

Will carry across the plains

The places that I'm dreaming of

Do they dream only of me?

There are places where they never sleep

And the circus never ends

I will take the Marylebone Coach

And be whistling down the wind

So I will take the Marylebone Coach

And whistle down the wind

Afterwards, we just drove away.

21.10.07

White Hills

Yellow daisies in the tough grass of the Chinese section. An ochre lichen grows over the tilting, dun-coloured stones, through which gleams the red painted into the inscribed characters that name the dead. A circular tower with a conical roof, a hearth within for burning paper money? Offerings? Small, like the grave tablets. Some of these men walked five hundred miles overland from Adelaide, digging wells along the way, living on sheep they bought from local farmers. They were very cheerful, singing as they marched to New Gold Mountain to make their fortunes. Wind sighs in the Gallipoli pines. The yellow fields stretch fenceless away into the purple and blue-black gums. A rosella flies up into the trees, iridescence glinting from its wings. A lone cry.

1.10.07

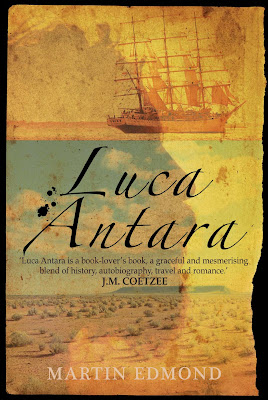

Heard last week that East Street have sold the UK? European? rights to Luca Antara to Oldcastle Books.

They've put this gorgeous new cover on it & dropped the subtitle ... & there's to be a hardcover edition. I've never had a hardcover edition before.

Never had a book published outside the antipodes either.

26.9.07

Fata Morgana

Have just received a publisher's advance. To write a book about Ludwig Becker, the German artist/scientist who went with Burke and Wills on their doomed expedition to, and across, central Australia. It's not a large amount of money but enough, with the help of the credit left on my card, to make a pilgrimage to Becker's grave. I'm going with an artist friend who'll bring a camera and use it, and other means, to document the trip visually. We'll fly to Melbourne in about ten days times and there look at the art works Becker left behind from the expedition, and other sojourns in Australia - especially Tasmania. Then we'll set out to retrace his journey, which, for various reasons, differed from that of the more famous Burke and Wills. Ultimate destination is a spot on the Bulloo River in south west Queensland, not far from Thargomindah, where Becker died and was buried. I'll keep a journal of the two week trip and write it up with various digressions, mostly into the life Becker led before he came to the antipodes, and what he did here in the ten years before he enlisted with the mad Irishman ... it's pretty ... exciting ...

Image: Border of the Mud-Desert near Desolation Camp. March 9t 1861. Ludwig Becker.

19.9.07

13.9.07

dark of the moon

One star shines through a hole in the leaves of the tree outside this building. What star? Don't know. What kind of tree? A gum, it flowers whitely or yellowly, profligate, often; though not now. The street so quiet this could be the future. The one without us in it. A cat walks along a wall, stops, walks some more. That makes two. Survivors. Cat pauses again, looks up, a green flash from its eyes. Does it see me? Or just ... sense an alien presence there. Street seems somehow soft, rubbery. As if it would sigh and give a little if you walked down it. Cars made of charcoal latex. The White Lady like a ghost, she hasn't moved once since I sold her, weeks ago now. Feel like ringing the new owner up and berating him for neglect. Except what about my own neglect, almost total. I've never seen a night quite like this, so absent, so empty, so unforeboding. The world as it must be when there's no-one here to see it. The yellow star still hangs in the hole in the heaven of the tree, making me think of Magritte, those trees with doors in them that open upon marvels. Light spilling from the darkness within. So quiet, did I say that? Now I will discard my butt end, swallow the last of the wine and step off the balcony into the air. You will see the trail of my tears hiss softly across the leaves. Some slight disturbance blur in the branches and then I will be gone. Into the umbra of that yellow star. Into the aching mysterium. The nebulium.

9.9.07

The Pink

and White

and White

Terraces

... as painted by Charles Blomfield (who some say never saw them). More here.

and White

and White

Terraces

... as painted by Charles Blomfield (who some say never saw them). More here.

2.9.07

smokin' dust

If it had not been for ... if it had not been ... if it had not ... if it had ... if it ... if ...

That's, in six words, the essence of, why, why & how. & who with.

The chance not taken, or taken, takes us, whither.

Dark eyes in the night, out on the smoking bridge. Littered with unsipped glasses of bourbon & coke.

Fugitive crackle of some kind of plastic, sewn into the seams of an old black dress, 1940s.

The taxi I didn't take, looking down from the bridge, I saw it pull away, someone else in the back.

The garden of forking paths.

Sometimes you stand there & know you are there, at the nodal point. Sometimes you don't. Know. But you're there, nevertheless. Never. The. Less.

Didn't even realise Chris smoked. Lifted fags for both of us, from some bloke who worked for a university press. Then left.

Leaving me ... there. At the nodal point.

Where if decays into something more like its opposite. Whatever the opposite of if is.

Inevitability.

Think war might be like this? You gallop down a path that was just the faintest trace of a white thread on the night, some possibility that delayed you for the infinitesimal amount of time it takes for a decision to be made.

Or not made.

That taxi. Those dark eyes. Another ... smoke.

& there I am, going ...

That's, in six words, the essence of, why, why & how. & who with.

The chance not taken, or taken, takes us, whither.

Dark eyes in the night, out on the smoking bridge. Littered with unsipped glasses of bourbon & coke.

Fugitive crackle of some kind of plastic, sewn into the seams of an old black dress, 1940s.

The taxi I didn't take, looking down from the bridge, I saw it pull away, someone else in the back.

The garden of forking paths.

Sometimes you stand there & know you are there, at the nodal point. Sometimes you don't. Know. But you're there, nevertheless. Never. The. Less.

Didn't even realise Chris smoked. Lifted fags for both of us, from some bloke who worked for a university press. Then left.

Leaving me ... there. At the nodal point.

Where if decays into something more like its opposite. Whatever the opposite of if is.

Inevitability.

Think war might be like this? You gallop down a path that was just the faintest trace of a white thread on the night, some possibility that delayed you for the infinitesimal amount of time it takes for a decision to be made.

Or not made.

That taxi. Those dark eyes. Another ... smoke.

& there I am, going ...

30.8.07

26.8.07

dust devil

A dream of dust. It lies along the edges of all the bookshelves, on the tabletops in the study, the sitting room, the kitchen, it congeals on the ledges of the skirting boards and on the wainscotting, on the pelmets, everywhere. The glass-topped dresser. The windowsills. I run my forefinger along the flat wooden surfaces, pushing up cloudy skirls of grey and brown and letting them fall onto the dun-coloured carpet which, later, I think (in the dream) I will vacuum. The windows themselves are golden with grime that filters the late afternoon sun to revelations of dust and one day I will hang out of those that open and clean them too. Or inscribe them with sigla encoded perhaps with the secrets of time. The dream has a soundtrack, it is Mazzy Star, Hope Sandoval's melancholy voice drifting in and out of the debris: I could possibly be fading / Or have something more to gain / I could feel myself growing colder / I could feel myself under your fate / Under your fate. Never knew until this actual moment that that was what she was singing. This moment of awakening, slipping across the purple sheets, rolling out from under the blue duvet, looking for those dust devils. And they're gone. Or rather, not here. It's just the ordinary familiar chaos of things. Feathers, stickers peeled off apples, sequins fallen from the kaleidescope, crumbs. Where has the dream dust gone? What is dust anyway? Planetary dust. Dust of light, dust of skin, dust of books. Curators are advised no longer to wear white gloves, the abrasion of cotton causes as much damage to paper surfaces as the oils in the whorls of fingertips. Dust of tears, what's left after the liquid evaporates and only the salt remains. The heart's dust. Or the galaxy's. It was you breathless and tall / I could feel my eyes turning into dust / And two strangers turning into dust / Turning into dust ...

A dream of dust. It lies along the edges of all the bookshelves, on the tabletops in the study, the sitting room, the kitchen, it congeals on the ledges of the skirting boards and on the wainscotting, on the pelmets, everywhere. The glass-topped dresser. The windowsills. I run my forefinger along the flat wooden surfaces, pushing up cloudy skirls of grey and brown and letting them fall onto the dun-coloured carpet which, later, I think (in the dream) I will vacuum. The windows themselves are golden with grime that filters the late afternoon sun to revelations of dust and one day I will hang out of those that open and clean them too. Or inscribe them with sigla encoded perhaps with the secrets of time. The dream has a soundtrack, it is Mazzy Star, Hope Sandoval's melancholy voice drifting in and out of the debris: I could possibly be fading / Or have something more to gain / I could feel myself growing colder / I could feel myself under your fate / Under your fate. Never knew until this actual moment that that was what she was singing. This moment of awakening, slipping across the purple sheets, rolling out from under the blue duvet, looking for those dust devils. And they're gone. Or rather, not here. It's just the ordinary familiar chaos of things. Feathers, stickers peeled off apples, sequins fallen from the kaleidescope, crumbs. Where has the dream dust gone? What is dust anyway? Planetary dust. Dust of light, dust of skin, dust of books. Curators are advised no longer to wear white gloves, the abrasion of cotton causes as much damage to paper surfaces as the oils in the whorls of fingertips. Dust of tears, what's left after the liquid evaporates and only the salt remains. The heart's dust. Or the galaxy's. It was you breathless and tall / I could feel my eyes turning into dust / And two strangers turning into dust / Turning into dust ...

images of dust devils on mars from wikipedia (worth looking at - the second is a moving picture)

lyrics from Into Dust, Mazzy Star, on the album So Tonight That I Might See

24.8.07

Don't ...

Once knew a woman who always said Don't. Meaning, don't say don't. To me. Because if you do, I will inevitably want to do the don't thing. This was true, particularly in regard to drugs and alcohol. Don't go out and score today meant going out to score. Don't have another drink meant having another drink. Or three. Didn't work for everything, eg sex. Don't make love to me ... what sort of a come-on is that? Used to wonder about the psychology of this. Was it Catholic? Something to do with sin, confession & forgiveness? If so, how? Or was it something else? Perhaps a notion that any attempt to establish authority over her would always be resisted. Funny logic though. She was Irish. Told her one time what Oscar Wilde said: I can resist anything except temptation. She laughed. But she could resist temptation, at least some of the time. What she couldn't resist was being told not to do something. Then she had to do it. For a long while I couldn't understand this state of mind. Now, quite suddenly, I do. Don't.

20.8.07

Warwick Roger

While I was in Auckland, up at the library with Michele going through various boxes of the Red Mole archive, I came across a clipping from Wellington's Dominion newspaper from, I think, 1976. It was a judgment by the Press Council upholding a complaint I'd made on behalf of the magazine Spleen against said newspaper. The Dominion was obliged to publish the judgment in full and so they had, even though it was highly critical of their conduct and in particular of the conduct of one of their journalists. Here's the story:

That year in Wellington film maker Richard Turner was preparing a documentary about Black Power, the gang, and as part of those preparations he'd recorded taped interviews with some of the gang members. He offered one of these tapes to Spleen, which regularly featured transcriptions of interviews with all sorts of people, from bus drivers to performance artists. I transcribed it myself and prepared the transcript for publication. It appeared in issue 6 under the title Yeah, we're bringing in the real shit. So far so good.

Subsequent to the interview, one of the interviewees was charged with being a party to a murder that happened in Wellington's Te Aro. A drunk had racially abused some Black Power members and they had beaten him to death. Horrible crime.

One Monday morning, before the case went to trial, the Dominion's billboard advertised a five part series of articles, to run every day for a week, that was called Anatomy of a Murderer. Each in the series was published beneath banner headlines on the editorial page of the paper. They carried the byline of a journalist called Warwick Roger. The bulk of the material in the articles was in fact lifted, holus bolus, without permission and without attribution, from Spleen.

Well you can imagine how we felt. Not just at the rip off, also at the flagrant disregard for the Black Power member's rights: he had been charged but not yet tried. Since he hadn't been found guilty, why was the Dominion calling him a murderer? The matter was sub judice and the articles surely in contempt of court.

The founding editor of Spleen, Alan Brunton, and I went in high dudgeon down to the Dominion's offices and bearded the editor of the paper in his den. I remember Alan, who could be fearsome when in full cry, telling the editor he was a casuist and then looking at the editor and realising that, while he knew he was being insulted, he didn't actually know what the word meant. We wanted the paper to withdraw the articles but they would not. We wanted to see the journalist in question but he didn't show. The most they would do was acknowledge the source of the material, which they did, grudgingly, on the Thursday I think it was.

We could of course have sued the Dominion and we would probably have won; but we didn't have the kind of money you need to hire lawyers. So we took the complaint to the Press Council instead.

At no stage in this imbroglio did we meet or otherwise communicate with the journalist, Warwick Roger. Not for the want of trying however. He clearly avoided us and, in my own case, has avoided me down all the years since. He has, however, just reviewed one of my books, Waimarino County, for a magazine called North & South. The review is short, contains some glaring inaccuracies (he says the book is in two parts; it's actually in four) and, after some rather fulsome praise of the first section, dismisses the rest of the book as perhaps cathartic for me but pretentious and largely incomprehensible to him. He doesn't mention the three essays on Alan Brunton's life and work that are contained therein. Well, why would he? He probably didn't read them. Mr Roger's review emboldened another NZ reviewer, Sue Edmonds at the Waikato Times, to say that she too found much of the book consisted of pretentious intellectualism.

It would be drawing a long bow to suggest that those far off events in 1976 had any influence on this review, more than 30 years later; anyway it doesn't matter. One thing I will say: to be found largely incomprehensible by a man of Roger's stature, with his peculiar understanding of journalistic ethics, is perhaps no bad thing.

That year in Wellington film maker Richard Turner was preparing a documentary about Black Power, the gang, and as part of those preparations he'd recorded taped interviews with some of the gang members. He offered one of these tapes to Spleen, which regularly featured transcriptions of interviews with all sorts of people, from bus drivers to performance artists. I transcribed it myself and prepared the transcript for publication. It appeared in issue 6 under the title Yeah, we're bringing in the real shit. So far so good.

Subsequent to the interview, one of the interviewees was charged with being a party to a murder that happened in Wellington's Te Aro. A drunk had racially abused some Black Power members and they had beaten him to death. Horrible crime.

One Monday morning, before the case went to trial, the Dominion's billboard advertised a five part series of articles, to run every day for a week, that was called Anatomy of a Murderer. Each in the series was published beneath banner headlines on the editorial page of the paper. They carried the byline of a journalist called Warwick Roger. The bulk of the material in the articles was in fact lifted, holus bolus, without permission and without attribution, from Spleen.

Well you can imagine how we felt. Not just at the rip off, also at the flagrant disregard for the Black Power member's rights: he had been charged but not yet tried. Since he hadn't been found guilty, why was the Dominion calling him a murderer? The matter was sub judice and the articles surely in contempt of court.

The founding editor of Spleen, Alan Brunton, and I went in high dudgeon down to the Dominion's offices and bearded the editor of the paper in his den. I remember Alan, who could be fearsome when in full cry, telling the editor he was a casuist and then looking at the editor and realising that, while he knew he was being insulted, he didn't actually know what the word meant. We wanted the paper to withdraw the articles but they would not. We wanted to see the journalist in question but he didn't show. The most they would do was acknowledge the source of the material, which they did, grudgingly, on the Thursday I think it was.

We could of course have sued the Dominion and we would probably have won; but we didn't have the kind of money you need to hire lawyers. So we took the complaint to the Press Council instead.

At no stage in this imbroglio did we meet or otherwise communicate with the journalist, Warwick Roger. Not for the want of trying however. He clearly avoided us and, in my own case, has avoided me down all the years since. He has, however, just reviewed one of my books, Waimarino County, for a magazine called North & South. The review is short, contains some glaring inaccuracies (he says the book is in two parts; it's actually in four) and, after some rather fulsome praise of the first section, dismisses the rest of the book as perhaps cathartic for me but pretentious and largely incomprehensible to him. He doesn't mention the three essays on Alan Brunton's life and work that are contained therein. Well, why would he? He probably didn't read them. Mr Roger's review emboldened another NZ reviewer, Sue Edmonds at the Waikato Times, to say that she too found much of the book consisted of pretentious intellectualism.

It would be drawing a long bow to suggest that those far off events in 1976 had any influence on this review, more than 30 years later; anyway it doesn't matter. One thing I will say: to be found largely incomprehensible by a man of Roger's stature, with his peculiar understanding of journalistic ethics, is perhaps no bad thing.

19.8.07

13.8.07

The White Lady

Yesterday I sold my car. To a guy who lives round the corner. She's still parked where I left her, outside the building next door ... but she's not mine any more. I haven't quite understood this yet. I bought her in 1991 with some money I got for a film that was going into production. So, what's that? Sixteen years ago? Always meant to restore her to original condition, never did. She was a sort of talisman that decayed into a relic. I thought she would be hard to sell. She wasn't. I thought that, once she was sold, I would never see her again. Not so. Curiously, the fellow who bought her is a film person. Has directed a feature called Roseberry 7470. That's the final of all the postcodes in Australia. Down in Tassie somewhere. He also runs the Sydney Underground Film Festival. This car has appeared in a feature film, called Violet's Visit. Perhaps her career in film is not over. She always took me where I was going, mostly up and down the east coast of Australia; she also gave me many sleepless nights as I shunted helplessly between the ideal and the real. One more sleepless night last night and perhaps that's the end of it. Or ... not ...

photo by C. Garth Thompson

11.8.07

returned mail

The frenzy passes, leaving a silvery trail, like longing, in which are glints of lapis. The scent of blue hyacinths. Mail continues to come back, read or unread, I can't remember. I could work it out but why? They are like fragments of some old conversation, drifting out towards the stars, forever whispered and forever unheard ... unless some unimaginably delicate sensor in the Andromeda Nebula picks up the transmission: You are so perceptive ... it hears and then cancels the thought. Wrong. And after all it isn't as if I haven't been here before. Examine the dark interior for signs of shame. Minimal. Regret? Yes, but isn't that a constant? A sweet sadness that isn't always there, for what might have been, for what shimmered delusively into view for an hour or a day then fell into starry dust. Recall a friend telling me how, as soon as she leaves work, the characters in her head begin again their long extrapolation of the possibilities. One of them will be herself. Or a version thereof. Others will be unreal, or thus far unreal. Still others will be ... real but not as they are in the world. I am myself perhaps sometimes among them; though not as I am. Nothing is ever lost but much passes away unheard, unseen. Unthought? The un thoughts gather at the margins of sense, a great hissing cloud like the dead. The unborn. What might have been. What could yet be. What was. Is.

7.8.07

4.8.07

For a while now I've been wanting to write about the flour mill. Called Mungo Scott. I used to see its sign from the train when I came into town from the Central Coast to write a film script that would never be made. It was called Blue Fields but the flour mill sign was ambiguous, a C or a G? It still is: Munco or Mungo? When I was younger I had a dog called Mungo, after Mungo Park the Scots explorer. Some kind of retriever though I never hunted him. I did fabricate a pedigree, said he was a Lord Park Hound. Some of my classmates thought it was so and that was the first time I knew the quandary of a liar believed. Have re-sought the experience, never without trepidation, always with the wariness deliberate ambiguity breeds. Yesterday when I paused on the bridge I could smell the wheat smell on the damp air. Was reminded of when we used to feed the chooks, throwing them handfuls of the grain. Many pigeons on the wires and a train on the line, stopped, a red light on the last truck. The red light was my baby, the blue light was my mind. Or should that be the other way round. There was no blue light, but I paused anyway, thinking the train might pull out of the siding and go but it didn't. The ambiguity I live in now is not deliberate but no less confusing for that. I know I will never know the truth. Once I was on the bridge thinking about birds on wires as musical notes, Ezra Pound via Leonard Cohen if such a thing can be. Well of course it can. Another time, a Sunday, the pigeons were feeding on wheat thrown down on bare ground outside for them. There were spotted doves too but they are shy. Where is this going? The flour mill is painted cream, it is large, with well-tended gardens, functioning security but here and there, as in all industrial complexes, there are strangely neglected parts, sheds and things: I am particularly drawn to those corrugated iron structures that cling to the high and far off roofs of the silos, what are they for? Who works, or lives, in them? Sometimes at night there are lights burning there. If I went out now, would I smell the wheat smell, see the grain swelling in the wet air, the bursting of the seed, the radical and the plumule? Is it my heart that goes like that, whether I am at the bridge over the flour mill or here, now, writing? Swollen, I mean, bursting, sending a root down one way and a green shoot up the other? And how could it be otherwise? You cannot live by bread alone.

26.7.07

24.7.07

23.7.07

Go into the study, I say, your slippers are at the ends of your beds; but the slippers, black with Chinese dragons on the tops where the toes go, are not there and none of us know where they have gone. It's like the crocodile letter opener, disappeared into a vacuum or black hole that can't, in any ordinary understanding of the world, exist. I, desgraciadamante, / el dolor crece en el mundo a cada rato, / crece a treinta minutos por secundo, paso a paso ... The tear of muscle in the lumbar region, on the left side, I mean, the hot wire that runs from humerus to radius, the exquisite burning of the styloid process. Tenosynovitis. RSI. OOS. We humans spend ninety percent of our time indoors, most of it sitting down somewhere or other. We are seldom naked and we don't know much about our bones. I want to be buried upright in the earth, at or near the place I was born, with a tree, perhaps a towai, planted over me. They use the bark for tanning hides, or they used to. We had a big one in our garden, it's not there any more, neither tree nor garden, and it's hard to see how I'd get back in time. A wormhole, perhaps. Down there with the slippers, the letter openers, the other lost things, flints and bones, the strange fungi that grow under Five Finger Trees ... Jamás tanto cariño doloroso, / jamás tan cerca arremetió lo lejos, / jamás el fuego nunca / jugó mejor su rol de frío muerto! I buy the kids new shoes, Ug boots with Bart Simpson on the sides for the younger one, Volleys for the older, who never wore his slippers anyway; he runs and leaps all the way home, admiring them, and doesn't take them off for hours. I put a deposit down on a new desk, this one I'm at is four centimetres lower than the recommended height, it's a table top with the legs sawn off, placed on a base from some other structure, I've held onto it for sentimental reasons only, how stupid is that? It belonged to a friend who has died, he matched the two ill-matched parts, sanded down the top and painted the base green, I repainted it black afterwards, I like sitting and writing where he sat and wrote or painted or perhaps supped on one of the many whiskeys he liked ... Pues de resultas / del dolor, hay algunos / que nacen, otros crecen, otros mueren, / y otros que nacen y no mueren, otros / que sin haber nacido, mueren, y otros / que no nacen ni mueren (son los más) ... we walk over to Leichhardt to buy books, in Berkelouw's the top ten places in the top ten are all filled by the same book, I won't say it's name, I haven't read any of them, in this I'm guided by my son who says they're no good, he's reading The Ranger's Apprentice series at breakneck speed. The other one likes Tin Tin, he chooses The Shooting Star, soon he'll have the complete set. They sit on a bench at Petersham railway station platform side by side reading. No steam train comes through, just a Millennium that doesn't stop and, much later, a Silver Passenger train that does. They won't let me cross the road to look at my new desk in the window of the second hand shop, they want to get home and continue reading while I make potatoes in their jackets for lunch ... Señor Ministro de Salud: ¿qué hacer? / !Ah! desgraciadamente, hombres humanos, / hay, hermanos, muchísimo que hacer.

quotations from: Los nueve monstruous by CÉSAR VALLEJO

quotations from: Los nueve monstruous by CÉSAR VALLEJO

18.7.07

15.7.07

what bird is that?

This morning, very early, before it was properly light, a bird called three times outside my window. What bird? I do not know; and yet I think I know all the birds that come around here, and their cries and songs. I'd been very late to bed, must have only been asleep for a couple of hours and I didn't wake properly. It wasn't a dream but in my half-dreaming state I seemed to be on the green-black slope of some far moorland, with the grey sea in the distance; or perhaps on the nether side of Ruapehu, looking out over the Rangipo plains towards the Kaimanawa; or ... I don't know. Then, just now, I was over at The Imaginary Museum reading Jack's latest post on the metamorphoses of the Metamorphoses and saw the cover of Ted Hughes' book Crow. The augurous bird whistling out my window might not have been a crow but its cry did bring to mind lines from that book that I memorized years ago: Dawn's Rose / Is melting an old frost moon. // Agony under agony, the quiet of dust, /And a crow talking to stony skylines ...

14.7.07

Over at Passages, Jacky Bowring's site, there's three photos of churches. The second is of one I know well. After a visit there in 1980, I wrote about it:

On a high green hill just outside Raetihi stands a Ratana church with twin domed towers upon which Arepa and Omeka, Alpha and Omega, are traditionally written. We stopped the car by a clay bank on one side of a cutting through the hill, stepped through the fence and climbed up a steep slope luxuriant with gone-to-seed grass towards the church.

Flags were flying on the marae next door—the Ratana flag, the Union Jack, the New Zealand flag, the Rising Sun. A light rain was falling as we walked over to where a young girl sat on the steps of the whare kai. She got up and went into the building. Peering after her into the gloom, I could see the long trestle tables covered with newsprint, the orange and yellow and green and red of the bottles of soft drink, the big plates of sliced buttered bread. A man with red-rimmed eyes and a distracted air came out. He looked doubtful.

The church? he said. It might be a bit difficult, you know, because we're having a tangi here today.

He stood on the porch looking out at the falling rain.

I don't know about the church, he said at last. I'm not a Ratana, see. There's a fella in there who's a Ratana. He might be able to help you more than I can.

He turned and, stooping slightly, went back into that dark interior. He came out again with a younger man, short, stocky, well built. This man radiated that inner certainty and strength called mana. The deep, regular lines round his eyes were like the ravines we had seen up on the mountain.

Well, it's a bit difficult really, the Ratana began. It's not us younger ones you see, it's the old people ... maybe not if it was any old time, but today, with this tangi on for one of our elders ...

Both men lit cigarettes, Rothmans, using a Bic suspended in a leather pouch on a thong round the Ratana’s neck. A scatter of kids drifted nearer.

How many go to the church? Barry asked.

About two, said the Ratana. No, I mean it. Two or three.

The church is down there now, said Redeye, gesturing with his thumb towards the town.

Down the pub, said the Ratana.

A thin woman came up, trailing a couple more kids. She lifted a smoke from Redeye.

I'm going home now, she said. There's no place for kids here.

She rubbed her thumb and forefinger together. Redeye reached into his pocket and pulled out some crumpled notes. He offered her a two, but her bony fingers extracted a five instead. While this was going on, another character appeared out of the darkness of the building. He was very black. The whites of his eyes glittered strangely in the gloom of the afternoon. He looked like a Dravidian.

Hey, why don't you get Him to turn the tap off up there? he said to the Ratana, jerking one hand towards the sky.

It would just come down again somewhere else, was the equable reply.

The Dravidian’s eyes gleamed. He went off down the side of the building muttering to himself. There was a pause.

You can go in, but you can't take photographs. You can photograph the outside and you can have a look inside.

Inside was a little piece of heaven. The same segmented five-pointed star inside the cusp of the crescent moon was carved into the pew ends. Each segment of the star has its own colour: blue for the Father, white for the Son, red for the Holy Ghost; purple for the Angels and gold for the Mangai, T. W. Ratana. Everything in the church was painted, even the altar, which was strewn with flowers. On the wall behind it were murals, copies of the originals at the temple at Ratana.

They had been painted by a youth who was held to be a reincarnation of the prophet's son, Arepa; like Arepa, like Ratana's son Omeka, this boy died when his work was done. The murals tell the story of the movement, especially during the 1920s, when a crusade went out into the world: to the USA, to the League of Nations, to England to see the king. At Geneva the New Zealand representative to the League made sure the delegation was not received. In London, George V, King-Emperor, refused Ratana an audience.

In Japan, however, he was greeted with great ceremony by Bishop Juji Nakada of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Gifts were exchanged, marriages made. Ratana taught that both Maori and Japanese were among the lost tribes of Israel. The idea grew that Ratana had married the Maori race to the Japanese race, had enlisted their support for Maori grievances and prophesied the coming of a world war between the non-white and white races: this is why the Rising Sun still flew over Te Puke marae next to the Haahi Ratana at Raetihi.

from Waimarino County & other excursions, title essay, part VII

On a high green hill just outside Raetihi stands a Ratana church with twin domed towers upon which Arepa and Omeka, Alpha and Omega, are traditionally written. We stopped the car by a clay bank on one side of a cutting through the hill, stepped through the fence and climbed up a steep slope luxuriant with gone-to-seed grass towards the church.

Flags were flying on the marae next door—the Ratana flag, the Union Jack, the New Zealand flag, the Rising Sun. A light rain was falling as we walked over to where a young girl sat on the steps of the whare kai. She got up and went into the building. Peering after her into the gloom, I could see the long trestle tables covered with newsprint, the orange and yellow and green and red of the bottles of soft drink, the big plates of sliced buttered bread. A man with red-rimmed eyes and a distracted air came out. He looked doubtful.

The church? he said. It might be a bit difficult, you know, because we're having a tangi here today.

He stood on the porch looking out at the falling rain.

I don't know about the church, he said at last. I'm not a Ratana, see. There's a fella in there who's a Ratana. He might be able to help you more than I can.

He turned and, stooping slightly, went back into that dark interior. He came out again with a younger man, short, stocky, well built. This man radiated that inner certainty and strength called mana. The deep, regular lines round his eyes were like the ravines we had seen up on the mountain.

Well, it's a bit difficult really, the Ratana began. It's not us younger ones you see, it's the old people ... maybe not if it was any old time, but today, with this tangi on for one of our elders ...

Both men lit cigarettes, Rothmans, using a Bic suspended in a leather pouch on a thong round the Ratana’s neck. A scatter of kids drifted nearer.

How many go to the church? Barry asked.

About two, said the Ratana. No, I mean it. Two or three.

The church is down there now, said Redeye, gesturing with his thumb towards the town.

Down the pub, said the Ratana.

A thin woman came up, trailing a couple more kids. She lifted a smoke from Redeye.

I'm going home now, she said. There's no place for kids here.

She rubbed her thumb and forefinger together. Redeye reached into his pocket and pulled out some crumpled notes. He offered her a two, but her bony fingers extracted a five instead. While this was going on, another character appeared out of the darkness of the building. He was very black. The whites of his eyes glittered strangely in the gloom of the afternoon. He looked like a Dravidian.

Hey, why don't you get Him to turn the tap off up there? he said to the Ratana, jerking one hand towards the sky.

It would just come down again somewhere else, was the equable reply.

The Dravidian’s eyes gleamed. He went off down the side of the building muttering to himself. There was a pause.

You can go in, but you can't take photographs. You can photograph the outside and you can have a look inside.

Inside was a little piece of heaven. The same segmented five-pointed star inside the cusp of the crescent moon was carved into the pew ends. Each segment of the star has its own colour: blue for the Father, white for the Son, red for the Holy Ghost; purple for the Angels and gold for the Mangai, T. W. Ratana. Everything in the church was painted, even the altar, which was strewn with flowers. On the wall behind it were murals, copies of the originals at the temple at Ratana.

They had been painted by a youth who was held to be a reincarnation of the prophet's son, Arepa; like Arepa, like Ratana's son Omeka, this boy died when his work was done. The murals tell the story of the movement, especially during the 1920s, when a crusade went out into the world: to the USA, to the League of Nations, to England to see the king. At Geneva the New Zealand representative to the League made sure the delegation was not received. In London, George V, King-Emperor, refused Ratana an audience.

In Japan, however, he was greeted with great ceremony by Bishop Juji Nakada of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Gifts were exchanged, marriages made. Ratana taught that both Maori and Japanese were among the lost tribes of Israel. The idea grew that Ratana had married the Maori race to the Japanese race, had enlisted their support for Maori grievances and prophesied the coming of a world war between the non-white and white races: this is why the Rising Sun still flew over Te Puke marae next to the Haahi Ratana at Raetihi.

from Waimarino County & other excursions, title essay, part VII

11.7.07