Reading Robert Hughes' Goya which I approached initially with great enthusiasm. Despite the undoubted virtues of Hughes' convict book The Fatal Shore, I've always thought his best writing has been about art and his best book, of those I've read, the collection Nothing If Not Critical which is informed, incisive, resonant, brief ... lapidary, even. So it is a surprise and a disappointment to find this ... a plod. And hence, a slog. There's something painfully dutiful about the way the history of Spain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries is narrated, something equally rote about the way Hughes marks off the works Goya made contemporaneously with these events. Occasionally the prose takes off, almost always when a work is being discussed, but these odd flashes and gleams are rare enough. Much of the rest is both dull and repetitive, as if, like so many books these days, not enough time was given over to editing the text. Also the balance between word and image seems wrong, there is so much writing that the illustrations, while high quality, are just too small for the detail to be properly seen, so that I often find myself peering into the shadows looking for something Hughes remarks upon, unable in fact to see it properly. All of these defects are bearable, plus Goya is such an extraordinary artist and his story so compelling, that I will certainly read the book to the end, though not without regret for what might have been.

But there's something else, which I guess could be described as Hughes' personal intrusions into the narrative. These begin in the first chapter, Driving into Goya in which Hughes reprises some aspects of the very bad car accident he was in in Western Australia in 1999, specifically the long and painful recovery period during which, he says, he 'met' Goya. This haunting and the attendant suffering, finally showed him how he could write his long contemplated book about the artist. So far, so good. But for anyone living in Australia who follows the news, that long-running episode of Hughes' accident and the aftermath does not recall the author's nobility of suffering and humility of insight so much as it does his pettiness, spite and anger at what he saw as his mistreatment by the State authorities and, by extension, his country as a whole. He doesn't go on here as much as he has in other places but what he does say is enough to taint, not so much his inquiry, as his tonality. And once that tone is established, it keeps recurring.

Nothing if not opinionated might be another way to describe Hughes and I'm comfortable with that so far as it relates to the subject of his book ... but do we need to hear what he thinks about the current fashion for Thanksgiving turkeys in the United States? Is it necessary for him to ask us to imagine him in bed for an afternoon with The Naked Maja? Do we want to hear his opinions about the West Australian government? Can't help thinking if there were less of this kind of bluster, less repetition, less Hughes, we could have had a lot more Goya. As it is, I have to read the book with another, one that has decent sized reproductions, to hand, so I can see the paintings, etchings and drawings. But, inevitably, not everything in the one is in the other and I end up frustrated.

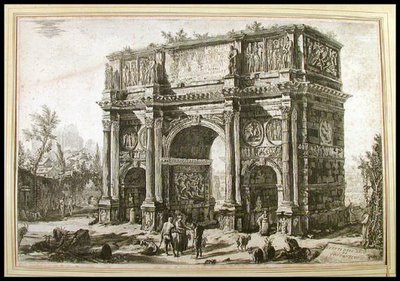

Those bombasts, like Hughes, who turn against their country the way he has are not so very different in the end from those others who wrap themselves in the flag and proclaim, over and over, that this is the best country in the world. On other hand, he is a formidable scholar and a very learned man, so it might be better to end with a speculation he gives us quite early on in the piece: the young Goya sharing lodgings with Piranesi in Rome, circa 1770-1.

the Goya self portrait dates from the time of the illness in the early 1790s that left him deaf; the Piranesi was done in and of Rome about 1770.

No comments:

Post a Comment