28.2.06

The Fitzgerald

Dave Harding, our bass player, was down in Baja, Mexico and he met this guy from Wyoming, an expatriate of sorts, a guy who had found a large bail of cocaine and hid it out in the desert. He and Dave became friends, his name was Richmond Fontaine. Then Dave went over to his place one night and the man was gone. All his stuff still there, but no one saw him again. No one knew anything ... more

27.2.06

optimism

Last night, while trying my best, as a dinky-di auzzie, to be optimistic about the Past (I've more or less given up on the future and the present is so beguiling in itself I don't ever want to ask the half empty/half full question here) I realised that the glass paper weight on one of the two cd racks that was propping up the Vincent van Gogh self-portrait that came as an insert in Saturday's Sydney Morning Herald would look better on top of the other (taller) cd rack. Somehow as I was making the switch the paper weight slid through my fingers and fell onto the low table below, the one that held the cd player, cd racks, loose cds, mp3 player, a few books, a few other bits and pieces. It was a glass-topped table and the glass table top ... exploded. It sounded like a gun going off. Slivers of glass embedded themselves in me, one in a finger, another in a toe but I didn't notice that immediately, because the cd player had unaccountably started playing Richmond Fontaine's The Warehouse Life - "broken, blond 'n' lost 'n' blue" - and also, the Ralph Hotere/Bill Manhire collaboration Pine, which I'd just received as a review copy, was among the debris ... this fine printing of 16 images/poems retails for $300.00 unsigned ($800.00 signed) and although I don't think I'll ever sell it, I did feel like rescuing such a notionally valuable work (same price as The Times Atlas of the World) from the wreckage ... that was when I saw the blood. Well, the wounds are not too bad and the carpet's pretty stained already and the book was marked on the cover when I got it, now it's even more marked and has a Past as well which I will continue to try to be optimistic about; besides, I decided I like Richmond Fontaine a lot more than I thought I did and have been playing them/him all day today as I extract shards from the carpet and re-arrange the furniture and, yes, it's true, I didn't need that extra table after all. Now if I could just get the haunted look off Vincent's face ...

24.2.06

23.2.06

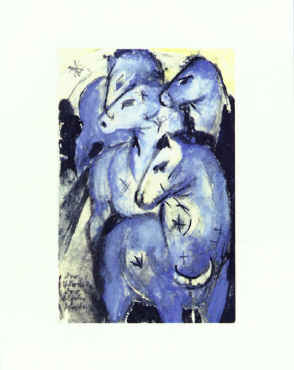

Der Turm der blauen Pferde

This:

I would guess is a study for this:

which, not having seen it before today, I am desolated to learn, was already lost and gone before I was born, being one of those works, part of Entartete Kunst, that did not survive WW2.

A favourite, evidently, of Oz poet James McAuley, one of Ern Malley's dads.

As for the study ... don't know.

Franz Marc was killed in 1916, in WWI, three years after he made The Tower of Blue Horses.

I would guess is a study for this:

which, not having seen it before today, I am desolated to learn, was already lost and gone before I was born, being one of those works, part of Entartete Kunst, that did not survive WW2.

A favourite, evidently, of Oz poet James McAuley, one of Ern Malley's dads.

As for the study ... don't know.

Franz Marc was killed in 1916, in WWI, three years after he made The Tower of Blue Horses.

21.2.06

... falling on my head like a new emotion ...

Michael P. Stevens at Pedestrian Happiness offers a link to an article about saudade that is valuable for a few reasons: it makes a plausible distinction between saudade and nostalgia - saudade longs for a future, impossible though it might be; suggests a possible historical context for the genesis of this feeling; explores cognate terms in other languages like Basque, Spanish & Brazilian ... most of all, perhaps, encourages speculation upon the notion that we do evolve emotionally, that there are new feelings that in time will be named ...

20.2.06

I took my troubles down to Madam Ruth

Thing is, growing up where and when I did, was one of the last of the pre-TV people. Didn't even see a TV set until I was about 12 and we had to move from a remote mountain village to a rather less remote small rural town before that could happen ... was in the window of an electrical goods shop and there were half a dozen people, adults and kids, standing round looking at this thing in the window. The first program I remember seeing was a drama about river boat gamblers on a Mississippi paddle-steamer. In black and white, natch. What we had before that was the movies (every Saturday), the radio and a piano. A record player too, but it was hardly ever used and the only two records I remember my parents owning were My Fair Lady with Rex Harrison, Audrey Hepburn and/or Julie Andrews and Stanley Holloway and an album of William Clausen, live. (He was some kind of Scandinanvian lounge lizard who did folk-and-novelty-songs plus what passed for witty commentary in between.) The radio wasn't for music, it was for news, current events, sports and drama - the weekly serials that we sat around on chairs listening to in the evening. For music, there was the piano, which was played just about every night when I was a small child and was also the centre of every party, of which there were quite a few in our house in the 1950s, less and less in later years. So, music on the radio and TV, which arrived in my life more or less simultaneously, were truly revelatory, not least because they were beaming out at us kids, not our parents. At the time when I started listening, the sister next up from me in years was a fully fledged Beatles fan (she liked Paul) and the one up from her, the eldest, had a few singles - Trini Lopez, Pat Boone - that she used to play sometimes. I started secondary school in 1965 and one of the highlights, early in the year, was the Gala Day, during which the cafeteria was blacked out and lit with flashing lights and a band played - and that was the second revelation after the radio. Live music. That day, a Saturday, we all crowded into the cafeteria and danced for what seemed liked hours but might not have been. The song they played over and over was Love Potion #9 by Leiber and Stoller that was a hit for The Clovers in 1959, for The Searchers in 1964 and The Ventures in 1965, which might have been the version this Gala Day band, whoever they were, was covering but more likely it was The Searchers'. Still remember staggering out into the bright afternoon light with a sense of absolute astonishment at how wonderful everything was in there and how boring it all looked out here. Clearly, though I didn't know it at the time, this was also my first drug experience.

19.2.06

rock 'n' roll cluedo

... but the song that really set me on the path was Gerry & the Pacemaker's How Do You Do It? I was 12 or 13, and still remember the when, where & with what: Sunday evening, in the bathroom, with the radio. In those days we lived in a rented flat above the Chemist's shop on Main Street, Greytown. The old mantle radio was not in the bathroom, probably one of my sisters was listening to it in her bedroom but somehow that song just came out and claimed me for its own. I heard it perfectly, can hear it now. Haven't yet gone looking for it in the ether. In a way I wish it had been the Rolling Stones' Paint it Black or the Yardbirds' Shapes of Things or even A Whiter Shade of Pale, the first single I bought ... yeah, left it on the back seat of my mother's Hillman Imp, it buckled in the sun, never played it ... but they all came later. Yet, in the anthropology of 60's pop, that song (How Do You Do ... ) has a place. Written by Mitch Murray, it was offered in the first instance to The Beatles, who knocked it back because they wanted to record a song of their own: Please Please Me it was called. Mitch also wrote I'm Telling You Now for Freddy and the Dreamers; Ballad Of Bonnie and Clyde for Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames; and Billy, Don't Be A Hero for Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods.

18.2.06

three songs

As a friend pointed out the other day, LimeWire is perfect for retrieving those old songs you loved way back when, you can just pull them out of the ether without needing to search through bins or buy whole compilation albums full of other stuff ... so in that spirit I went searching yesterday for three faves from the sixties. Intrigued to realise as I looked that, although these songs have been part of my (mental? musical?) life for forty odd years, I'd never owned a recording of two of them and the third I'd bought only belatedly, after the singer (Dusty) died, and lost soon afterwards. Which means, I guess, that my memory of each is formed entirely by radio listening and probably over a relatively short period of time, refreshed intermittently and randomly since. Because they are so clear in my mind ... nor was I in the least bit disappointed when I recovered the originals, they sounded just the same and just as good. The surprises were in the lyrics, which I'd misheard here and there, as you do, or never figured out properly.

Anyway, they are:

Walk Away, Renee - The Left Banke; written by Michael Brown about Renee Fladen, the girlfriend of another band member, bassist Tom Finn (that must have caused tensions in the band room; their next two hits were also by Brown about Fladen) and sung by Steve Martin, a recent migrant to New York from Puerto Rico; released 1966 and subsequently covered by all sorts of people, most famously The Four Tops; but The Left Banke version has a plaintive quality no subsequent renditions quite got, because of Martin's voice I think. The lyric I'd never understood in this is the awkward last four words of:

Now as the rain beats down upon my weary eyes

For me it cries

The First Cut Is the Deepest - PP Arnold; was surprised to learn that this was written by Cat Stevens; released on Andrew Oldam's Immediate label in London in mid-1967; another much covered song of course, but apart from a reggae version by I can't remember who, none of the others comes close to this one; there's a moment in it where you really do hear PP Arnold's voice doubt that it will ever again be possible as she sings but if you want I'll try to love again ... I'd never figured out the terminations to the spendidly twisted last two lines of the chorus, which go:

But when it comes to being lucky he's cursed

When it comes to loving me he's worst

Goin' Back - Dusty Springfield; written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King for Dusty to sing and released also in 1967, this was a song that always made me feel gloriously sad, like the most ancient 15 year old on the planet, lamenting my lost youth when it had barely even begun ... now, a few decades later, when its message might seem more appropriate than it did then, it just makes me feel 15 again. Revelatory lyrics? The first line of this couplet:

Let everyone debate the true reality

I�'d rather see the world the way it used to be

How'd they get away with that?

Anyway, they are:

Walk Away, Renee - The Left Banke; written by Michael Brown about Renee Fladen, the girlfriend of another band member, bassist Tom Finn (that must have caused tensions in the band room; their next two hits were also by Brown about Fladen) and sung by Steve Martin, a recent migrant to New York from Puerto Rico; released 1966 and subsequently covered by all sorts of people, most famously The Four Tops; but The Left Banke version has a plaintive quality no subsequent renditions quite got, because of Martin's voice I think. The lyric I'd never understood in this is the awkward last four words of:

Now as the rain beats down upon my weary eyes

For me it cries

The First Cut Is the Deepest - PP Arnold; was surprised to learn that this was written by Cat Stevens; released on Andrew Oldam's Immediate label in London in mid-1967; another much covered song of course, but apart from a reggae version by I can't remember who, none of the others comes close to this one; there's a moment in it where you really do hear PP Arnold's voice doubt that it will ever again be possible as she sings but if you want I'll try to love again ... I'd never figured out the terminations to the spendidly twisted last two lines of the chorus, which go:

But when it comes to being lucky he's cursed

When it comes to loving me he's worst

Goin' Back - Dusty Springfield; written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King for Dusty to sing and released also in 1967, this was a song that always made me feel gloriously sad, like the most ancient 15 year old on the planet, lamenting my lost youth when it had barely even begun ... now, a few decades later, when its message might seem more appropriate than it did then, it just makes me feel 15 again. Revelatory lyrics? The first line of this couplet:

Let everyone debate the true reality

I�'d rather see the world the way it used to be

How'd they get away with that?

17.2.06

Oh, well, that's the excitement over for the week. 5000 words, give or take a few hundred (I only keep daily tallies). Some of it I like quite a lot, some I'm not sure about, and some I know will need a good going over sooner or later. But that's alright. This is not going to be a long book, only 50, maybe 60 thousand words so I'm well on the way now ... meanwhile the editor's report on Luca Antara came through this week, it begins: This is superb. How about that? Best of all, she thinks the weaknesses are what I think the weaknesses are, which will make working together so much easier. We have a good understanding already, this is the third book we've done although the second one the publisher stood between us so we didn't actually have any direct communication. The numbers ... Luca is 100,000 plus and I want to get it down below that magic figure if it's at all possible, losing maybe 5000 words? Or, to put it another way, a week's work. Happy to let it go ...

15.2.06

lambda

For years now I've been haunted by a heresy. One I can't get out of my mind. It's that I don't believe in the Big Bang. Once, in the audience at a literary festival being addressed by an Eminent Philosopher, I put up my hand in question time and suggested that the Big Bang was an appropriate cosmological metaphor for a civilization that had invented the atomic bomb and was gratified when the Eminent Philosopher's jaw dropped. But only for a moment; she soon consigned the notion to the reject pile of loopy ideas and went on to other things.

Anyway ... have just read an article by Neil DeGrasse Tyson called Gravity in Reverse (in The Best American Science Writing 2004) which gives the clearest explanation I've yet come across of the Cosmological Constant (= lambda), Dark Matter and Dark Energy. I won't (can't) go into the details but the statistics are extraordinary and the (possible) conclusion genuinely uncanny: the cosmos is (they say) 73% Dark Energy, 23% Dark Matter and 4% ordinary stuff. It's the Dark Energy, which appears to arise out of a vacuum, that seems to be driving expansion:

As a consequence, anything not gravitationally bound to the neighbourhood of the Milky Way will move away from us at ever-increasing speed ... Galaxies now visible will disappear beyond an unreachable horizon ... beyond the starry night will lie an endless void, without form ... darkness upon the face of the deep.

So far so good. But what about this -

Dark energy, a fundamental property of the cosmos will, in the end, undermine the ability of later generations to comprehend their universe. Unless contemporary astrophysicists across the galaxy keep remarkable records, or bury an awesome time capsule, future astrophysicists will know nothing of external galaxies - the principal form of organisation for matter in our cosmos. Dark energy will deny them access to entire chapters from the book of the universe.

Here, then, is my recurring nightmare: Are we, too, missing some basic pieces of the universe that once was? What part of our cosmic saga has been erased? What remains absent from our theories and equations that ought to be there, leaving us groping for answers we will never find?

On the other hand, there's nothing here that doesn't accord with our experience of life as she is lived.

(the image is a picture of globular cluster M13)

14.2.06

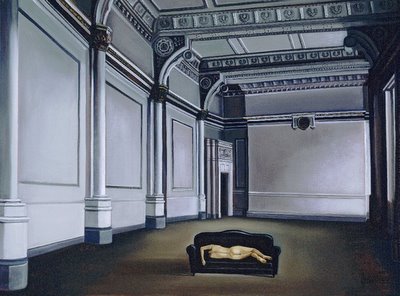

This is a painting by Anne Wallace called Reverie. More of her work can be seen here. Worth a look ...

13.2.06

Counting words, counting laps, can seem like exercises in futility. What, exactly, is being counted? Or rather, when the tally's in, what does the amount signify? Quite often when I'm swimming I lose count of the laps, it's easy to do, the state of mind is meditative, drifting, waterly, if that's a word, wholly antithetical to the harsh progression of numerals. When I do, lose count that is, it's always on an odd lap ... 9, 11, 13, 15 ... which suggests it's on the evens that I mostly drift off. Then I am faced with a dilemma: if this is either 13 or 15, which shall I choose it to be? (I'm only ever out by two.) The Roundhead in me insists on choosing the lower number, while the Cavalier says what the hell, let's just get off and do something that doesn't require effort. Roundhead always wins and for him it's a source of pride that, even if the count is wrong, it's wrong by more not less. While Cavalier says what the fuck, who cares, let's go to the wine shop and see what reds they have on special this week. When it comes to counting words, more proximate and more strange, they more or less agree : Roundhead will accept 964 if that's what it is when I (we) run out of puff, while Cavalier is usually thinking of that odd graceful flourish or complex manouvre which we wouldn't have got if we'd stopped at 703.

10.2.06

Weel May The Keel Row

In the 1930s in Dorrigo, New South Wales, a flute-playing farmer kept a young lyrebird as a pet for several years. In all that time the bird learned to imitate just one small fragment of the farmer's flute-playing ... the farmer released the bird into the forest. Thirty years later, lyrebirds in the adjacent New England National Park were found to have flute-like elements in their song, a sound not heard in other populations of superb lyrebirds. Further analysis of the song showed that the phrase contained elements of two popular tunes of the 1930s, "Mosquito Dance" and "The Keel Row". As lyrebirds can sing two melodies simultaneously, through several generations this population had created its own distinctive territorial song blending the two melodies into a single compressed phrase ... it is now seventy years since the lyrebird learned these fragments, and today the flute song has been heard a hundred kilometres from the original source. A human song is spreading through the lyrebird world ...

from : Why Birds Sing by David Rothenberg, Allen Lane, 2005

from : Why Birds Sing by David Rothenberg, Allen Lane, 2005

8.2.06

shoe box full of grasshoppers

Easy enough to rewrite 'darg' as 'drag' I found myself thinking yesterday evening after coming back from a Writer's Guild function. I never usually go to these things and now remember why : they advertise that they are showing clips from a recently completed feature film but no-one knows how to work the equipment and when they do finally get it going, the quality is truly appalling, light falling on faces is garish pink, shadows are lime green, there are lines through every image; the writer/director barely apologises for this insult, instead, he radiates a kind of svelte boredom, I've made it all on my own and you could too if you were as handsome and talented as I am but, who cares, I'm going off to live in Europe for a while; while his script editor has up a full head of outraged steam, she can't wait to tell the assembled ignoramus writers how disastrous our ordinary day to day assumptions about our craft must be. When questions begin to be asked she has visibly to suppress her exasperation and speak with the kind of controlled simplicity you use for primary school kids; meanwhile the most alarming thing of all is the docility with which the ignoramus writers take it, you begin to suspect that if and when they get their turn on the podium, they too will behave in this manner. We were, I realised part way in, associate members of the guild, so not real writers yet, hence perhaps the obvious contempt we were held in. But why that contempt to begin with? Is it owed by those who have risen precisely because they suffered it before? Or is it a defensive reaction, a holding of the line against those who might also rise? Not clear. I was reminded of something a poet said of his home town, that living in Adelaide was like living in a shoebox full of grasshoppers. I'd rather be a bird, maybe a magpie or a crow.

7.2.06

darg mark

Darg isn't a word you hear in common speech anymore. I only know about it because I once lived in a Darghan Street, in Glebe, and a Scots-born friend suggested, speculatively, that the word was the origin of the street name. It is in the OED however, which says 1. a day's work; 2. a definite amount of work, a task and says it is a contraction of Middle English daywerk or daywark. I'm charmed though to learn that it is still in use in the lingo of Axemen in what seems an entirely appropriate usage: It came to be applied to the marks scratched on almost anything to signify that the person concerned had completed his tally ...

6.2.06

My Darg

So I went looking yesterday for something on the web about Conrad's writing regime, but all I found was a 1971 interview with Graham Greene where he complains that Conrad worked 12 hours a day whereas he can only manage an hour and a half. He also admits to obsessive word counting, making little marks on his day's work at 300, 600 and 900 words and giving up when he tops 1000. Presume he worked on a typewriter or maybe even wrote long hand, either way, that's a lot of time spent counting. Now we have computers to do that for us ... I try to get over the 1000 mark myself and not to think too hard about the quality of those thousand words, many of which are 'and' and 'the' and 'was' and so on. Darg btw is an old convict word, probably originally Scots, it referred to the duties a man or woman had to complete as part of their obligation to the State (usually personified as an individual s/he was bonded to) before they could go off and work for themselves ... or get drunk ... or go for a swim ... or whatever. Which is what, my darg over for today, I'm going to do now.

4.2.06

Often when I'm writing I don't read properly. I don't even browse properly. I pick books up and put them down again or I find myself staring at the same sentence for moments on end, not knowing what it means, or I get to the end of a page and have no idea what the words my eyes have passed over are trying to say ... on the other hand, bits and pieces stick in my mind even though frequently I can't remember where I read them ... here's a few ... Joseph Conrad wrote 300 words a day. He said writing is a miserable vocation ... there is a Verlaine poem with an epigraph from a lost work of Rimbaud's, it reads: Rain fell softly over the city ... Giorgio de Chirico was born at Volos, the port from which Jason set sail for Colchis in the Argo ... the first thing ever broadcast on ABC Radio, in 1932, was a lyrebird singing ... starlings came into North America because an eccentric in New York determined to release every bird mentioned in Shakespeare to the New World ... yesterday was the 75th anniversary of the Napier Earthquake ... there is a book, just published, which is a dictionary of one letter words; it has over a thousand entries and the largest entry is for X.

3.2.06

machinations

It’s a long time since I wrote anything at all with a pencil or a pen: filling out forms, signing documents, scrawling notes incomprehensible to anyone else.

First typewriter : a Consul portable bought in 1970 for $30.00 in a 2nd hand shop on K Road. Same place where I got my compleat Shakespeare (onionskin paper) for rather less – six dollars? Still got the Shakespeare.

Purchased, new, in Wellington, an Imperial portable that I carried all around the world and gave eventually to a Frenchman in Sydney not long after I got here. He was meant to be helping me with my André Breton translations but once he had the typewriter, lost interest. Curled his lip and went back to La Belle France.

Bought a Brother electric that was ok.

An electronic Olivetti that had some kind of vestigial memory, gave me nothing but trouble. Still have some pieces I typed on it but. Nice typeface. Pica.

Moved into a squat, no electricity, bought a 2nd hand 1950s Olivetti cast iron frame desktop manual ($80.00), a beautiful machine. Let it go a few years back when I got sick of carrying it from place to place every time I moved. Bad decision, they’re worth a lot now and they never break down.

First computer : an Amstrad 9512, a disastrous investment even though I loved it at first. Had a bizarre daisywheel printer that was so user unfriendly most of what I wrote stayed on disk; later discovered disks incompatible with those of all other machines; wrote my first real book on it but subsequently lost approx. five year’s occasional writing when I sent the disks off to some old Amstrad freak to get 'translated' and they never came back. Luckily most of it no good.

An early Apple Mac portable, a Powerbook 150. Loved it more than the Amstrad, with which it coexisted for a while. Gave me RSI, hunched over the small keyboard for hours. Was stolen just after I sent away the ms of my second book; lost about three years of occasional writing, some of which was ok. I think.

First PC, assembled by a sometime friend who worked in a computer warehouse and put it together for her then girlfriend, who left her for someone else. Bought in haste after the theft of the Mac. Cost a grand. Crashed on average once an hour, sometimes once a minute … endless problems. Wrote my third book on it but nothing else ever came to fruition even though there was a lot. A beige box, left by the side of the road.

A Dell. I phoned Penang in Malaysia with my specs, they sent them to a warehouse in Sydney, the machine arrived on the doorstep not too long after that. Wrote the beginning and the end of Luca Antara on it, the middle was done on a brand new HP at the University of Auckland. The Dell's still going, it’s what my kids use for whatever they get up to in cyberspace.

This machine, a G5 Mac. I hope and pray …

First typewriter : a Consul portable bought in 1970 for $30.00 in a 2nd hand shop on K Road. Same place where I got my compleat Shakespeare (onionskin paper) for rather less – six dollars? Still got the Shakespeare.

Purchased, new, in Wellington, an Imperial portable that I carried all around the world and gave eventually to a Frenchman in Sydney not long after I got here. He was meant to be helping me with my André Breton translations but once he had the typewriter, lost interest. Curled his lip and went back to La Belle France.

Bought a Brother electric that was ok.

An electronic Olivetti that had some kind of vestigial memory, gave me nothing but trouble. Still have some pieces I typed on it but. Nice typeface. Pica.

Moved into a squat, no electricity, bought a 2nd hand 1950s Olivetti cast iron frame desktop manual ($80.00), a beautiful machine. Let it go a few years back when I got sick of carrying it from place to place every time I moved. Bad decision, they’re worth a lot now and they never break down.

First computer : an Amstrad 9512, a disastrous investment even though I loved it at first. Had a bizarre daisywheel printer that was so user unfriendly most of what I wrote stayed on disk; later discovered disks incompatible with those of all other machines; wrote my first real book on it but subsequently lost approx. five year’s occasional writing when I sent the disks off to some old Amstrad freak to get 'translated' and they never came back. Luckily most of it no good.

An early Apple Mac portable, a Powerbook 150. Loved it more than the Amstrad, with which it coexisted for a while. Gave me RSI, hunched over the small keyboard for hours. Was stolen just after I sent away the ms of my second book; lost about three years of occasional writing, some of which was ok. I think.

First PC, assembled by a sometime friend who worked in a computer warehouse and put it together for her then girlfriend, who left her for someone else. Bought in haste after the theft of the Mac. Cost a grand. Crashed on average once an hour, sometimes once a minute … endless problems. Wrote my third book on it but nothing else ever came to fruition even though there was a lot. A beige box, left by the side of the road.

A Dell. I phoned Penang in Malaysia with my specs, they sent them to a warehouse in Sydney, the machine arrived on the doorstep not too long after that. Wrote the beginning and the end of Luca Antara on it, the middle was done on a brand new HP at the University of Auckland. The Dell's still going, it’s what my kids use for whatever they get up to in cyberspace.

This machine, a G5 Mac. I hope and pray …

1.2.06

54

When I was wandering through Indonesia about 18 months ago, the book I had with me was Luther Blissett's Q. Luther Blissett was a five year plan which ended in 1999 but some of its participants decided to continue working together as Wu Ming. Their next book is called 54 ... finished reading it last night which was so hot and mosquito-ridden that I had trouble sleeping. The title refers to the year, 1954, during which the action takes place. It involves many things, including the fate of those Italians who fought in the Resistance, Lucky Luciano's heroin empire, Cary Grant's career as an actor, Tito's Yugoslavia, the post-war determination of the status of Trieste, the KGB ... but the heart of the book is day to day life in a small bar in Bolgona called the Aurora and more particularly the younger brother of the manager who is a barman there by day and a famous dancer by night. Robespierre - called Pierre - is the book's hero and the machinations by which he at last manages to find the freedom he craves are wonderfully plotted; while the central place in these machinations occupied by a state of the art American television set called a McGuffin Electric is wonderfully funny. Whereas Q was dark and bloody and mired in the desperate and desperately complex politics of the Reformation, 54 is light and airy as a Cary Grant movie, consistently amusing and yet never slight or anodyne ... it is extraordinary that five hands can make such a seamless work; you read in a state of perplexity as to how they did it? One of the most enjoyable things for me in the book is the portrait it gives, by way of a fragmentary biography, of Cary Grant, born Archibald Leach in Bristol - I didn't know he was a Brit originally. During 54 he is about to make a comeback in Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief so there is an engaging cameo of Hitch at work to be savoured as well. 54 is worth reading for its homage to a great actor alone but it is much more than that. Wu Ming! Woooo ...!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)