... or a stranger in cyberspace, perhaps. Can't think of a thing to say. It's because I've been on other jags. Like downloading as much of the Joe Strummer song catalogue as I can find on LimeWire (quite a lot). Or tracking the emerging field of Medical Humanities aka Artistic Medicine. Or imagining in forensic detail the progress of rust on my sadly disintegrating car. Or ...

When I was in NZ last month, I was reminded of the Landfall Essay Competition by an editor of the University press that publishes the magazine. Why I thought of a piece On Trains I cannot now remember. But I wrote it. Then, just as it was being finished I got an email from another University press about The Gift Book, a publication to celebrate the inaugural Book Month over there. It was the five grand per selection that caught my eye, so off I sent the just completed essay.

Then, in my delusive state I thought, what will I submit to Landfall if and when The Gift Book takes my trains? I must have had a head of steam up, I sat down and wrote a second essay, this one called On Film. The two are not dissimilar, they are autobiographical, memorious, evocative (I hope) rather than nostalgic. Almost a diptych. I enjoyed writing both immensely.

Well, last week, when The Gift Book let me know I hadn't made the short list, I was far more disappointed than I would have been if I hadn't stupidly allowed myself to hope ... and now I've got two essays and only one competition. So I thought, how would it be if I sent the one on film to the essay comp. and posted the other here, in stages, perhaps five, because it'll be too long otherwise and long things don't look well in cyberspace?

That way I could restore some life to this site and also allay the disappointment I felt about that particular train missing its station, as it were.

... thinking about it anyway. I may start tomorrow.

31.5.06

23.5.06

hoo dat?

In Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West he's called the Judge and at the end of the book, after he has murdered the Kid in an outhouse jakes, it is written: His feet are light and nimble. He never sleeps. He says that he will never die. He dances in light and in shadow and he is a great favourite. He never sleeps, the judge. He is dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die.

In Tom Waits' Black Wings he has no name, only attributes and a history: He once killed a man with a guitar string / He's been seen at the table with kings / He once saved a baby from drownding / There are those who say beneath his coat there are wings ... One look in his eyes / Everyone denies / Ever having met him ...

Same guy turns up in Talking Heads' Swamp: How many people do you think I am / Pretend I am somebody else / You can pretend I'm an old millionaire / A millionaire washing his hands / Rattle them bones, dreams that stick out / A medical chart on the wall / Soft violins, hands touch your throat / Everyone wants to explode ...

He's in a Dylan song too: Somebody seen him hanging around / At the old dance hall on the outskirts of town / He looked into her eyes when she stopped to ask / If he wanted to dance, he had a face like a mask / Somebody said from the Bible he'd quote / There was dust on the man / In the long black coat.

I walked forty seven miles of barbed wire, Bo Diddley sang. I use a cobra snake for a necktie / Got a brand new house by the roadside / Made out of rattlesnake hide / Got a brand new chimney set on top / Made out of a human skull / Now come on Baby take a walk with me / And tell me who do you love?

Who is that man?

In Tom Waits' Black Wings he has no name, only attributes and a history: He once killed a man with a guitar string / He's been seen at the table with kings / He once saved a baby from drownding / There are those who say beneath his coat there are wings ... One look in his eyes / Everyone denies / Ever having met him ...

Same guy turns up in Talking Heads' Swamp: How many people do you think I am / Pretend I am somebody else / You can pretend I'm an old millionaire / A millionaire washing his hands / Rattle them bones, dreams that stick out / A medical chart on the wall / Soft violins, hands touch your throat / Everyone wants to explode ...

He's in a Dylan song too: Somebody seen him hanging around / At the old dance hall on the outskirts of town / He looked into her eyes when she stopped to ask / If he wanted to dance, he had a face like a mask / Somebody said from the Bible he'd quote / There was dust on the man / In the long black coat.

I walked forty seven miles of barbed wire, Bo Diddley sang. I use a cobra snake for a necktie / Got a brand new house by the roadside / Made out of rattlesnake hide / Got a brand new chimney set on top / Made out of a human skull / Now come on Baby take a walk with me / And tell me who do you love?

Who is that man?

18.5.06

Today it's 25 years since I first came to Australia. I was thinking of working up a statement of what this might mean but somehow, in the event, the anniversary seems without any significance at all. Oh, well.

* * * * *

Meanwhile, this amused me. It's from a review, in Overland, of Chronicle of the Unsung (2004):

Imagine W. G. Sebald turned vagabond hippy.

* * * * *

I've always counted myself lucky that I didn't read Sebald until after I'd written The Resurrection of Philip Clairmont(1999), particularly the first section of that book. It meant I could recognise an affinity rather than fall under the spell of a (possibly overpowering) influence.

* * * * *

It was The Rings of Saturn, still, in my opinion, the best of his books, that I read, in a Harvill edition translated by Michael Hulse, with a cover that is a detail of a Whistler painting: Harmony in Blue and Silver, Trouville. At first it seemed strange to me, that choice of cover image, but not any more.

* * * * *

This book was published in 1998 but I don't remember when I bought it - 1999? 2000? - although I do remember where: at Clay's Bookshop in Potts Point. The German edition (1995), I found out recently, has a sub-title - English pilgrimage - omitted from the translation. I don't know why.

* * * * *

It was raining hard, the City looked grey and unappealing. It kept on raining for two solid weeks while I squelched back and forth from the Springfield Lodge in Kings Cross to the Combined Services taxi depot in Glenmore Road, Paddington, learning how to do that.

* * * * *

One day the sun came out and there, across the road from the hotel, was an old friend, Vic Filmer, sitting on a bench, talking to himself, as he is wont to do. I hadn't seen Vic for years. Come to thnk of it, I haven't seen Vic for years. I should give him a call.

* * * * *

Meanwhile, this amused me. It's from a review, in Overland, of Chronicle of the Unsung (2004):

Imagine W. G. Sebald turned vagabond hippy.

* * * * *

I've always counted myself lucky that I didn't read Sebald until after I'd written The Resurrection of Philip Clairmont(1999), particularly the first section of that book. It meant I could recognise an affinity rather than fall under the spell of a (possibly overpowering) influence.

* * * * *

It was The Rings of Saturn, still, in my opinion, the best of his books, that I read, in a Harvill edition translated by Michael Hulse, with a cover that is a detail of a Whistler painting: Harmony in Blue and Silver, Trouville. At first it seemed strange to me, that choice of cover image, but not any more.

* * * * *

This book was published in 1998 but I don't remember when I bought it - 1999? 2000? - although I do remember where: at Clay's Bookshop in Potts Point. The German edition (1995), I found out recently, has a sub-title - English pilgrimage - omitted from the translation. I don't know why.

* * * * *

It was raining hard, the City looked grey and unappealing. It kept on raining for two solid weeks while I squelched back and forth from the Springfield Lodge in Kings Cross to the Combined Services taxi depot in Glenmore Road, Paddington, learning how to do that.

* * * * *

One day the sun came out and there, across the road from the hotel, was an old friend, Vic Filmer, sitting on a bench, talking to himself, as he is wont to do. I hadn't seen Vic for years. Come to thnk of it, I haven't seen Vic for years. I should give him a call.

16.5.06

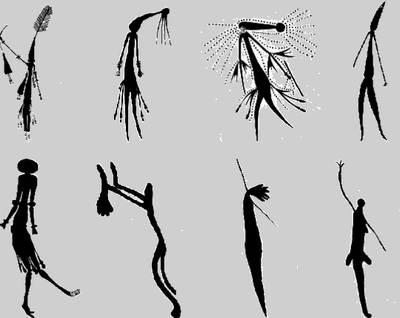

So I did track down the image of the Bradshaw dancer today. It's reproduced in :

The Art of the Wandjina : Aboriginal cave paintings in the Kimberley, Western Australia; I. M. Crawford; Melbourne : OUP in association with the Western Australia museum, 1968

where it is captioned:

‘A Bradshaw figure at Kalumburu Mission’

Kalumburu is a remote community in North West Kimberley, at the head of Napier Broome Bay, about as far away from anywhere else as you can get in Australia - but also, one of the closest points to Indonesia, specifically the island of Roti, just south and west of Timor, about 600 kilometres away across the sea.

I'm pleased about this, because in my storied voyage, I have the ship making landfall at Bigge Island, not so very far to the south in the Bonaparte Archipelago, and then heading north a ways before coming ashore on the mainland coast. Then there is an epic cross country trip to the north and the east, that ends where Darwin now is ... it is during this trek that the figure of the dancer, along with other Bradshaws, is seen on a cave wall.

One curious thing - 'authorities' deny that the Bradshaw figures show any sexual differentiation but I cannot see this particular figure as anything other than female - because of the elbows especially. I've never seen a bloke whose elbows go like that.

The Art of the Wandjina : Aboriginal cave paintings in the Kimberley, Western Australia; I. M. Crawford; Melbourne : OUP in association with the Western Australia museum, 1968

where it is captioned:

‘A Bradshaw figure at Kalumburu Mission’

Kalumburu is a remote community in North West Kimberley, at the head of Napier Broome Bay, about as far away from anywhere else as you can get in Australia - but also, one of the closest points to Indonesia, specifically the island of Roti, just south and west of Timor, about 600 kilometres away across the sea.

I'm pleased about this, because in my storied voyage, I have the ship making landfall at Bigge Island, not so very far to the south in the Bonaparte Archipelago, and then heading north a ways before coming ashore on the mainland coast. Then there is an epic cross country trip to the north and the east, that ends where Darwin now is ... it is during this trek that the figure of the dancer, along with other Bradshaws, is seen on a cave wall.

One curious thing - 'authorities' deny that the Bradshaw figures show any sexual differentiation but I cannot see this particular figure as anything other than female - because of the elbows especially. I've never seen a bloke whose elbows go like that.

11.5.06

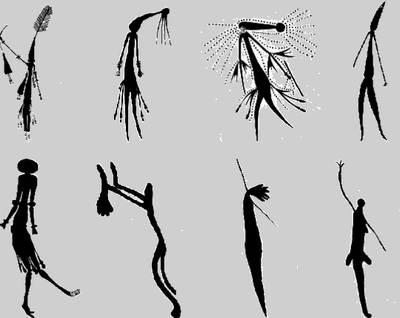

Many years ago, but I don't know how many - Fifteen? More? - I came across this image:

Nor can I remember exactly where I found it, obviously in some book or other because I still have a copy of the xerox I took. It's a graphic translation, by an unknown hand, of one of the so-called Bradshaw Figures, rock art of the Kimberley region in north west Australia.

The Bradshaws - named after a Joseph Bradshaw who first 'discovered' them in 1891 - are an enigma. They haven't been reliably dated and no-one has yet advanced a convincing explanation of who made them. They are very different stylistically from the wondjina tradition of painting that still survives up there.

To my eye, and this has of course been noted by others, they have affinities with figurative rock art tradtions in other parts of the world, particularly Africa. There have been more or less scholarly attempts to compare the Bradshaws with similar figures from both southern and northern (Algeria) African traditions.

This figure of a dancer, so graceful, insoucient, and free, was in many ways the original inspiration for Luca Antara, the book, she makes a brief appearance in it and I'm just now in discussions with the publisher which may lead to the inclusion of her image in the book as well. This would please me very much if it happens.

Some recent dates for the Bradshaws suggest they are about 17,000 years old, that is, they were made around the time of the last glacial maximum. It is a matter of fact that a great deal of land off the western and northern coasts of Australia was submerged as the ice melted and the ocean came flooding back. Large parts of what is now Indonesia also disappeared.

I've never been able to dismiss the possibility that the Bradshaws are the art of a culture and tradition that was more or less wiped out by the rising seas sometime in the last 10,000 years or so. I'm aware that there are various certifiable crackpots who have elaborated vast, fanciful dream towers about this thematic and I deny that I'm one of them.

But somebody made the Bradshaws and they show a sophistication which, while it certainly can't be used to support the idea of some Atlantis type lost civilisation, may still represent a flowering of a culture whose other artefacts and achievments now lie under the Timor Sea. This is likely to have been an indigenous Australian - ie Aboriginal - culture with strong ties to those of nearby Sundaland.

Some more images:

Nor can I remember exactly where I found it, obviously in some book or other because I still have a copy of the xerox I took. It's a graphic translation, by an unknown hand, of one of the so-called Bradshaw Figures, rock art of the Kimberley region in north west Australia.

The Bradshaws - named after a Joseph Bradshaw who first 'discovered' them in 1891 - are an enigma. They haven't been reliably dated and no-one has yet advanced a convincing explanation of who made them. They are very different stylistically from the wondjina tradition of painting that still survives up there.

To my eye, and this has of course been noted by others, they have affinities with figurative rock art tradtions in other parts of the world, particularly Africa. There have been more or less scholarly attempts to compare the Bradshaws with similar figures from both southern and northern (Algeria) African traditions.

This figure of a dancer, so graceful, insoucient, and free, was in many ways the original inspiration for Luca Antara, the book, she makes a brief appearance in it and I'm just now in discussions with the publisher which may lead to the inclusion of her image in the book as well. This would please me very much if it happens.

Some recent dates for the Bradshaws suggest they are about 17,000 years old, that is, they were made around the time of the last glacial maximum. It is a matter of fact that a great deal of land off the western and northern coasts of Australia was submerged as the ice melted and the ocean came flooding back. Large parts of what is now Indonesia also disappeared.

I've never been able to dismiss the possibility that the Bradshaws are the art of a culture and tradition that was more or less wiped out by the rising seas sometime in the last 10,000 years or so. I'm aware that there are various certifiable crackpots who have elaborated vast, fanciful dream towers about this thematic and I deny that I'm one of them.

But somebody made the Bradshaws and they show a sophistication which, while it certainly can't be used to support the idea of some Atlantis type lost civilisation, may still represent a flowering of a culture whose other artefacts and achievments now lie under the Timor Sea. This is likely to have been an indigenous Australian - ie Aboriginal - culture with strong ties to those of nearby Sundaland.

Some more images:

5.5.06

Among the many wonderful things seen, heard and done at Bluff / Rakiura, there are some that keep recurring in my mind's eye. Monday was a day off, we were in Oban and our time was our own. I decided to walk over to Maori Beach, a little to the north of Half Moon Bay, where I had been on my only previous visit to the island. It was a longer walk than I remembered, a good four hours there and back, the first part of it down sealed or metal roads where houses were and people lived. Then you went into bush, climbing through a link in a massive sculpture of an anchor chain coming out of the sea below. This because in Aotearoan mythology the North Island is a Te Ika a Maui, the fish pulled up from the ocean by Maui, the South Island is the waka or canoe he was sailing in and Rakiura, or Stewart Island, the anchor stone of that canoe. There were small birds waiting at the gate to welcome or to guide: a miromiro or tomtit:

and another I could not identify. The track undulated along the shore line, running down to small wild sandy beaches then climbing to the saddles of intervening headlands. On one of these saddles I was summoned by the sound of a tui:

singing close by and stopped to listen. The bird, a male, was sitting on a branch only a couple of metres away and, silhouetted as it was against the pale green underside of the leaves of forest trees, with glimpses of blue sea beyond, I could see it clearly both in the round and in profile. The tui is a mimic and I could hear in its song the calls of various other birds but the most extraordinary thing was that I could also see its tongue. It's a honey-eater, so its tongue is adapted for insertion into the cups of flowers with a brush like tip for gathering the nectar ... but from this vantage it was black and lithe and changeable, thinning and elongating beyond the tip of the beak to a dark rapier-like point then retracting and thickening to make the more guttural, throaty sounds, the clicks and clucks and churks. The bird was calling to another across the valley, so that after each aria it would pause and cock its head, waiting for the reply; and then reprise; and so on. I don't know how long I watched and listened, a long time, until it finished and flew away, with a flash of superb blue-green, in the direction of its rival or fellow. Later, at Maori Beach itself, wandering in soft muddy sand up the river bed at its further end, I saw a flurry in the shallows and scooped out of the water a baby flounder, hardly bigger than a fifty cent piece, which lay quite still in the palm of my hand until I re-immersed it in the inch deep water and it slid away and before my very eyes, as they say, turned itself into a piece of ribbed sea sand, almost imperceptible even though I'd watched it perform its act of camouflage; had I not, I'm certain I would not have been able to see it at all. There's a swing bridge over that river, leading on into the wilderness but, as it was last time, I didn't have time to go any further ...

4.5.06

A Found Text (found in the street in Bluff)

They had driven us out of the Bay View by playing Highway to Hell at max volume. The Anchorage, or is it the Golden Age, was closed. The lights were on in the Eagle but there was nobody home. The others turned back but I kept stupidly on up the stark unlovely midnight street. At the corner of Liffey and Gorre I was hailed by a shadow, blacker than the night behind it.

O farewell you streets of sorrow, it sang. O farewell you streets of pain.

Who are you? I asked.

Doncha know? the Shadow said. I’m Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth.

And what might you be doing here?

Waiting for the Tooth Fairy.

You’ll be waiting a long time.

I’ve already been waiting a long time, said Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth, but I can wait a little longer yet; and told me his tale:

When the time came for me to fall from Shane’s poor carious mouth and be gathered up and exchanged for silver, the Tooth Fairy swore she’d never seen such a specimen as me and would go to the ends of the earth before she’d lay her delicate fairy fingers upon it. ‘Alright then yer mouldy bitch,’ I said, ‘I’ll see you there.’ ‘I’d rather see you in hell,’ the Tooth Fairy said and disappeared in a puff of green smoke.

His story seemed lacking in a few essentials.

Is that it? I asked.

What more d’you want? he snarled, and I caught the unmistakeable stench of decay upon the clean night air. I’ve come all this way, to the ends of the earth, and I’m waiting for the Tooth Fairy to come herself and claim me for her own. Aw, Christ, it’s cold down here at the Bluff, and the pubs are all closed and the graveyards empty as well …

How do you pass the time? I asked, friendly as you like.

By singin’ songs and lookin’ at the girls, he replied, how do you think? There’s the two sisters, pretty as pictures, and I told one there was none more beauteous in the world than her, not even her sister; and then I told her sister the same. There’s the maiden of light and the maiden of dark. There’s the kelp woman who comes from the deep and wraps her salty self around me on nights when I’m lonesome …

Just then a black stretch limo drove past us down Gorre Street, heading for the signpost at the end of the world. Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth looked after it and swore.

That skivey git Joe Strummer, he said. Givin’ himself airs again.

What, I said, Joe’s down here too?

Aw, he only comes for the oysters. You’d think a dead man would have more respect than that but there you go, he was a diplomat’s brat all along.

There was nothing to be seen behind the limo’s tinted windows. I looked again at my interlocutor, trying to make out features or at the very least a shape in the sodium glare.

Why, I said, a moment later, you’re not really there at all, are you? You’re all cavity!

And what in hell did you expect? said Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth. Some kind of pearlie from the oyster? Some ivory for your mam’s brush to tickle? Some flossy Colgate fantasy?

A bright white light descended then, not before time, I thought it was the limo coming back, or maybe the police, who’d been cruising up and down Gorre Street all that long and boozy evening.

Lord be praised, it’s her at last, I felt rather than saw or heard the stench gape beside me. She’s gone and come for me at last.

The light formed a halo around that black shape, like an embrace, like enamel, like pulp in a jar.

Before the light re-ascended, I saw something I’ve not seen before and never wish to again: gangrene-black, mucous-green, pus-yellow and white as the jiggers a midnight drunk sees in his delirium tremens. This was not the tooth, mind, this was the Tooth Fairy herself, or who or whatever it was came to take him away:

You're a bum / You're a punk / You're an old slut on junk

Living there almost dead on a drip / In that bed

You scum bag / You maggot / You cheap lousy faggot

Happy Christmas your arse / I pray God / It's our last …

Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth sang.

O farewell you streets of sorrow, it sang. O farewell you streets of pain.

Who are you? I asked.

Doncha know? the Shadow said. I’m Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth.

And what might you be doing here?

Waiting for the Tooth Fairy.

You’ll be waiting a long time.

I’ve already been waiting a long time, said Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth, but I can wait a little longer yet; and told me his tale:

When the time came for me to fall from Shane’s poor carious mouth and be gathered up and exchanged for silver, the Tooth Fairy swore she’d never seen such a specimen as me and would go to the ends of the earth before she’d lay her delicate fairy fingers upon it. ‘Alright then yer mouldy bitch,’ I said, ‘I’ll see you there.’ ‘I’d rather see you in hell,’ the Tooth Fairy said and disappeared in a puff of green smoke.

His story seemed lacking in a few essentials.

Is that it? I asked.

What more d’you want? he snarled, and I caught the unmistakeable stench of decay upon the clean night air. I’ve come all this way, to the ends of the earth, and I’m waiting for the Tooth Fairy to come herself and claim me for her own. Aw, Christ, it’s cold down here at the Bluff, and the pubs are all closed and the graveyards empty as well …

How do you pass the time? I asked, friendly as you like.

By singin’ songs and lookin’ at the girls, he replied, how do you think? There’s the two sisters, pretty as pictures, and I told one there was none more beauteous in the world than her, not even her sister; and then I told her sister the same. There’s the maiden of light and the maiden of dark. There’s the kelp woman who comes from the deep and wraps her salty self around me on nights when I’m lonesome …

Just then a black stretch limo drove past us down Gorre Street, heading for the signpost at the end of the world. Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth looked after it and swore.

That skivey git Joe Strummer, he said. Givin’ himself airs again.

What, I said, Joe’s down here too?

Aw, he only comes for the oysters. You’d think a dead man would have more respect than that but there you go, he was a diplomat’s brat all along.

There was nothing to be seen behind the limo’s tinted windows. I looked again at my interlocutor, trying to make out features or at the very least a shape in the sodium glare.

Why, I said, a moment later, you’re not really there at all, are you? You’re all cavity!

And what in hell did you expect? said Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth. Some kind of pearlie from the oyster? Some ivory for your mam’s brush to tickle? Some flossy Colgate fantasy?

A bright white light descended then, not before time, I thought it was the limo coming back, or maybe the police, who’d been cruising up and down Gorre Street all that long and boozy evening.

Lord be praised, it’s her at last, I felt rather than saw or heard the stench gape beside me. She’s gone and come for me at last.

The light formed a halo around that black shape, like an embrace, like enamel, like pulp in a jar.

Before the light re-ascended, I saw something I’ve not seen before and never wish to again: gangrene-black, mucous-green, pus-yellow and white as the jiggers a midnight drunk sees in his delirium tremens. This was not the tooth, mind, this was the Tooth Fairy herself, or who or whatever it was came to take him away:

You're a bum / You're a punk / You're an old slut on junk

Living there almost dead on a drip / In that bed

You scum bag / You maggot / You cheap lousy faggot

Happy Christmas your arse / I pray God / It's our last …

Shane MacGowan’s Last Tooth sang.

3.5.06

te rau aroha

... have been a very long way away - & it was good - & part of me - does not want to come back ...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)